Abstract: Reflective practice is the primary component of the Partnership Brokers Associations (PBA)’s Accreditation Programme, where during the four-month mentored period, partnership brokers are required to keep a reflective log book to show evidence of their practice. Participants report mixed experience of reflective practice. For many partnership brokers, reflection is a new discipline, generating some uncertainty about the process, value, and indeed the discipline it requires to set aside time to reflect. However, when partnership brokers do get into reflection, they recognise the value from journaling for self-reflection and from having a critical friend and / or mentor. The author provides a personal perspective on reflection and reflective practice and explores some of the ways practitioners can integrate reflection into their partnership brokering practice.

The value of reflective practice for partnership brokers

As partnership brokers, we are encouraged to be reflective in our work and to use reflective practice and experiential learning for professional development. Indeed, reflective practice is the primary component of the Partnership Brokers Association’s (PBA)’s Accreditation Programme: during the four-month mentored period, partnership brokers are required to keep a reflective log book to show evidence of their practice.

Invariably, the time we spend on relationship-building and relationship management forms a key feature of such practice. In a partnership, we work with people from diverse backgrounds and perspectives. We manage complex and dynamic relationships and processes in setting up, facilitating, mediating, directing and managing partnering activities and understanding, influencing and coaching people. Tensions and issues can arise, sometimes confusing and unpredictable, and there is not always a logical or straightforward solution. We have to make professional judgments when faced with situations where there are no right or wrong answers. We come across interactions and experiences which make us pause and possibly re-evaluate how we see and deal with certain events. It is at times like these that reflection can be a valuable competency.

But what do we mean by ‘reflection’ and ‘reflective practice’? Why should partnership brokers develop it as a skill? How does it help us do our job better? How should we reflect – what strategies and tools do we use to guide our reflection?

Defining reflection and reflective practice

“Learning without thought is labour lost; thought without learning is perilous…by three methods we may learn wisdom: first, by reflection, which is the noblest; second by imitation, which is the easiest; and third by experience, which is the bitterest.” (Confucius)[1]

This Confucian perspective embraces three important aspects of reflective practice: learning from personal reflection, learning from others and learning from doing (action learning). Since his time, various scholars and practitioners in education and healthcare fields have put forward definitions for reflection. Here are a few which I find particularly useful:

| Reflection is ‘‘a form of mental processing with a purpose and / or anticipated outcome that is applied to relatively complex or unstructured ideas for which there is not an obvious solution.’’ (Moon 1999)[2] | “Reflection is an important human activity in which people recapture their experience, think about it, mull over and evaluate it. It is this working with experience that is important in learning.” (Boud et al)[3] |

| Reflection is “being mindful of self, either within or after experience, as if a window through which the practitioner can view and focus self within the context of a particular experience, in order to confront, understand and move toward resolving contradiction between one’s vision and their actual practice. Through the conflict of contradiction, the commitment to realize one’s vision, and understanding why things are as they are, the practitioner can gain new insights into self and be empowered to respond more congruently in future situations within a reflexive spiral towards developing practical wisdom and realizing one’s vision as a lived reality..” (Johns, 2004)[4] | |

| “Maybe reflective practices offer us a way of trying to make sense of the uncertainty in our workplaces and the courage to work competently and ethically at the edge of order and chaos…” (Ghaye, 2000)[5] | |

The terms ‘reflective practice’ and ‘reflective practitioner’ were coined by Donald Schön [6] whilst working in the field of professional learning and learning processes in organisations. He placed ‘reflection’ at the centre of an understanding of what professionals do: “the practitioner allows himself to experience surprise, puzzlement, or confusion in a situation which he finds uncertain or unique. He reflects on the phenomenon before him, and on the prior understandings which have been implicit in his behaviour. He carries out an experiment which serves to generate both a new understanding of the phenomenon and a change in the situation.[7]

Schön introduced two types of reflection – reflection-in-action, and reflection-on-action. The former occurs in real time where the practitioner tries to resolve a problem as quickly and as best as he / she can by analysing what they are observing, hearing or ‘feeling’ at the time. We are influenced by, and use, what has gone before, our previous experience. We try and draw upon the routines we already know. Learning is about making them more efficient for future use.

As partnership practitioners, we are probably more familiar with reflection-on-action – this occurs after the situation and focuses on spending time to explore why we acted as we did, what was happening or not happening, why and so on. In so doing, we develop sets of questions and ideas about our activities and practice as well as build up a collection or repertoire of images, examples, metaphors, theories and actions that we can draw upon. An evocative and imaginative description of the distancing function can be found in the ‘Pensieve’ described by Harry Potter’s creator, J K Rowling:[8]

“One simply siphons the excess thoughts from one’s mind, pours them into the basin, and examines them at one’s leisure. It becomes easier to spot patterns and links, you understand, when they are in this form.”

Making the case for reflective practice

All of the above provides a theoretical context for reflection. But how does it relate to the practicalities of partnership brokering: for instance, how does it help us do our job better? How does it fit in with the art and science of partnership brokering?

Hall [9] asserts that one sign of reflective practice is “recognising our own use and balance of the art and science of brokering. Knowing our interplay between our imagination; our insights, our possibilities-thinking and our analysis; our factual reporting; our ‘expertise’- having a feel for our own finger-print of the art and science of brokering”.

This is an important notion because it suggests that if we know our unique qualities and attributes as a partnership broker, we can improve our professional artistry through empirical, aesthetic, personal and ethical knowing. And by doing that we can go beyond just serving our own personal growth and development needs to delivering some impact on the quality of our relationship-building and relationship management – and hence, an improved outcome for both the partners and the partnership.

I found a very compelling case for the value of reflective practice being made by the “Ten C’s of reflection” proposed by Johns [10] (Table 1.0). These ‘Cs’ have been adopted as a framework for reflection for registered health practitioners in many parts of the UK National Health Service: practitioners are encouraged to use them when reflecting on the care and treatment they provide to their patients / clients and their carers. I can see a great deal of relevance of the ‘ten Cs’ in partnership brokering work because they cover both the personal engagement (art) and professional detachment (science) aspects of our brokering approach.

Table 1.0: Johns’ Ten Cs of Reflection

| Commitment | Accepting responsibility for self; the openness, curiosity and willingness to challenge normative ways of responding to situations |

| Contradiction | Exposing and understanding the contradiction between actual and desired practice |

| Conflict | Harnessing the energy of conflict within contradiction to take appropriate action. |

| Challenging and support | Confronting normative attitudes, beliefs and actions in a non-threatening way |

| Catharsis | Working through negative feelings |

| Creation | Moving beyond old self to novel alternatives to practice |

| Connection | Connecting new insights within the real world of practice |

| Caring | Realising desirable practice as everyday reality |

| Congruence | Reflection as a mirror for caring |

| Constructing personal knowledge in practice | Building personal knowledge with relevant theory |

Reflective practice is a core skill – it is an active, dynamic process to be honed through life-long experiential learning. In time, we get the reflective practice skill set where reflection becomes automatic, so much so that unless we stop to think about it, it is embedded in our professional persona.

As Tennyson (2008) [11] explains “with a bit of perseverance, reflective practice becomes a habit – and its impacts can be quite startling, leading to significantly more informed, confident and decisive decision making and behaviour. Reflective practitioners are therefore, in my experience, better equipped than non-reflective practitioners to conduct their external conversations (aka communication) far more effectively.”

Perhaps, therefore, it is not surprising that reflective practice has moved on from a ‘nice-to-have’ to an essential competency in the education and healthcare professions in many countries. Professional standards of proficiency, licensing and revalidation processes now require evidence of reflective practice. For example in the UK, it is part of the professional policies for doctors, nurses, midwives, psychologists, therapists etc.[12] Although there are risks associated with institutionalising reflective practice (for instance, producing superficial, bland reflections, perhaps slanted towards complying with existing or expected practice, especially if it is linked to performance evaluation) there is evidence to suggest that reflective practice is making a difference in therapeutic relationships.[13]

Developing a personal style

Reflection is a solitary learning activity, and while critical friends, mentors and others can help us do it, the insights and learning we achieve will ultimately be just ours. Which is probably why we see so much variety and individuality in the way we reflect. There is no standard way of reflecting.

We are instead influenced and motivated by our preferred learning style(s) and the modalities we use to learn, communicate and express ourselves. These in turn determine the reflective strategies and the tools we choose to support our reflection.

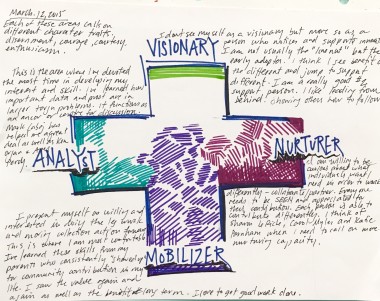

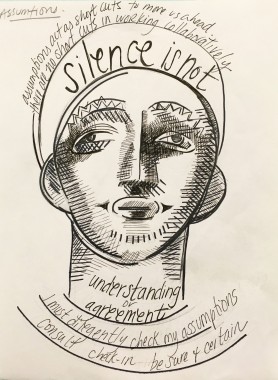

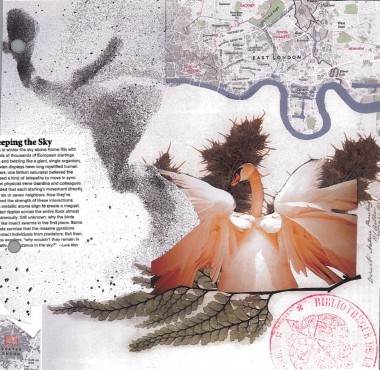

Some reflective practitioners are visual / spatial learners and communicators, preferring to use pictures, images, and spatial understanding. This is beautifully exemplified by extracts from the logbook of Elayne Greeley[14], an accredited PBA partnership broker who uses a variety of different techniques to reflect and review on her practice:

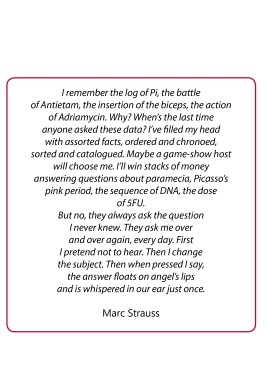

Many reflective practitioners are verbal / linguistic learners. Although we may use the occasional image or illustration, our dominant preference is for using words, both in speech and writing. Although much of the writing would be descriptive prose, some people may choose to express their thoughts in poetry and verse and in story-telling. I was not able to secure any examples from partnership brokers, but I have found some from the medical profession where creative reflection is now used as a resource for training doctors. Some medical schools found that their students felt the use of models of reflection constricting, whilst poetry, abstract painting and narratives freed up their expression allowing them to demonstrate the compassion for their patient under their care.[15]

For instance, the New York University School of Medicine has set up a LITMED[16] (Literature, Arts, and Medicine Database) to help students to “develop and nurture skills of observation, analysis, empathy, and self-reflection – skills that are essential for humane healthcare”. It includes poems penned by medical practitioners. I have chosen this light-hearted one, Log of Pi by Marc Strauss[17] who styles himself as an “oncologist-bard”, to illustrate the point. Strauss found very early on that he was writing poems about doctor-patient relationships, with one of the first poems he wrote being a “rhyme triplet in the voice of a noodgy, little old lady who was complaining about one of her doctors” :

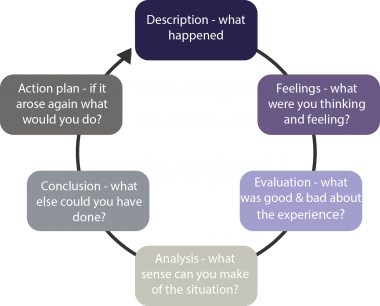

Such creative flair could by no means be everyone’s preference. Indeed, some practitioners would prefer a structured way of reflecting which uses models or pre-fabricated frameworks to guide them through the various stages of their reflective process. Over the years, a number of different models of reflection have been developed in different fields of education and professional practice. They vary in structure, format and emphases. Some view reflection as an orderly, cognitive, linear process, others as a multi-level, cyclical or spiral process and some see it as a more reflexive, value-laden, and context-dependent activity. Good reviews of the structured reflective models have been compiled by Mann, Gordon and MacLeod (2007) and by Ghaye and Lillyman (2008). [18] Some models are more suited to personal reflection where others tend to work better in a dialogical approach through collaborative reflection with a critical friend, mentor or a peer group review.

However, despite these differences, they share some common features around description of a situation, analysis, evaluation and alterative consequences for beliefs, behaviors and actions. The model that is most commonly used is Gibbs Reflective Cycle:[19]

Structured reflective models will not suit everyone. Some experimentation with different models might be necessary before you find one that you feel comfortable with. It is a matter of personal choice and / or the context in which you are working.

A practitioner with cognitive habits that are not linear and who does not ‘naturally’ and easily think about their work in an analytical process, will find Gibbs and other models restrictive. They will reflect better through creative reflection.

Increasingly, we may find that the notion of creative reflection challenges the action-reflection dichotomy of reflective practice and extend reflection beyond cognitive, retrospective models to encompass the exploration of possibility through play, image-making, writing, action methods and storytelling. It may also allow us to explore more unorthodox ways of connecting with our thoughts and feelings. For instance, some therapeutic practitioners advocate mindfulness as a reflective strategy. Kabat-Zinn’s (2012)[20] description of mindfulness as “paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally” while calmly acknowledging and accepting one’s feelings, thoughts, and bodily sensations has some resonance.

The value of reflection as a ‘silent’ conversation with the self is further illustrated by Tennyson (2008):[21] “once reflective practice becomes a habit, you move beyond the question-and-answer mode to an imagined conversation without words. You learn to still the chattering voice inside your head – full as it always is with impressions, memories, anxieties and unfinished business. You become better at resisting the relentless need to plan, to be logical, to be in control. You allow yourself to simply wait, and if you are lucky, images and ideas begin to emerge unquestioned and unasked for. It can be a truly creative and inspiring experience and can inform what you do and how you do it in a completely new way.

My hypothesis is that a good reflective practitioner increasingly knows how to ask themselves the right questions and to genuinely explore the real (if sometimes painful) answers – in other words, they have a particularly well-developed capacity to conduct productive “imagined conversations”. But an even better reflective practitioner is able to move beyond such imagined conversations to no conversations at all.”Preference for learning need not be a solitary activity of self-study: it can also be social – where we learn in groups or with other people. Partnership brokers who undertake the PBA training are introduced to the concepts of using critical friends – for dialogical reflection with others – as well as log books – for self-dialogues and self-evaluation. As much as we are able to frame questions to ourselves (it is sometimes difficult to do so), a critical friend may pose questions we may never have asked. These are questions that open up new space in our feelings and thoughts and our intentions to act. Powerful questioning can be practiced and enhanced.

Challenges of becoming a reflective practitioner

For many partnership brokers, reflection is a new discipline and many are unsure about how to ‘do’ it and what use it will be. Reflective writing requires some authenticity – to be able to disclose and share information (feelings, attitudes, motives, intentions etc.) with self and a critical friend / mentor; to have sufficient self-awareness of one’s own biases, beliefs, values and attitudes towards others; to be open to critical self-evaluation and not slip into self-absorption, defensiveness and so on.

Reflection requires discipline, to set aside time to reflect and some partnership brokers also find that keeping a journal can be a challenge, as illustrated by this quote from my own journal: “in my previous role in business, I would have had no time to keep a journal. No time to remove myself from the daily busy-ness to be still, to reflect on what I was doing or what was happening in the many relationships I seem to be juggling every day. When things went wrong, you were expected to be ‘decisive’ – rely on what had worked before to fix it as quickly and as best as you could. Moving into a partnership brokering role, I have had to learn to step back and think about what is going on – to feel and understand the vibrations and rhythms in this complex partnership before rushing into decisions….”.

Once partnership brokers overcome their initial reluctance and uncertainties and get into reflection, they admit to seeing the value from both journaling for self-reflection and having a critical friend and / or mentor for dialogical reflection.

As accredited partnership broker, Rita Dieleman[21], relates: “I have come to love my daily entries about my intentions, what actually happened and my reflections, because they provide me with better insights, than I would have with only thinking about it. That’s why I have the intention of writing some reflections like that every (larger) project. Before the project starts, I will write down what my intentions are for that specific project, especially with regard to my brokering activities. During the project I will describe what it is actually happening, and reflect on it. After finalization of the project I will analyse to what extent what happened overlaps with my intentions, what changed and why, what the impact of my brokering role has been and how I look back on it. I know it doesn’t take that much time and it provides me with great tangible insights. At the same time it works as a kind of reminder to pay attention to the art-side, if I fall back to my natural habit of hard-core evaluator. Of course it will be different without a mentor to help me make most out of my reflections.”

Reflective writing as a tool

A reflective or learning journal can help bring structure and focus to reflection, analysis and action and it creates an opportunity to create richer, meaningful content.[23] This can be about oneself, the partner, the team you are working with, the partnership or your own institution (operations, policies, culture) and even the broader trends in the international development field.

Reflective writing is a useful way of documenting feelings, observations, insights, lessons learnt, and action planning. In particular, it can help the practitioner in the following ways:

- To stand back from yourself and question your behaviours and attitudes and make sense of feelings and emotional responses when dealing with difficult situations / ’difficult people’;

- Through writing honestly, to improve self-awareness of own motives, attitudes beliefs; and challenge own assumptions and perceptions;

- To recognise the importance of being able to frame a problem before trying to solve it; to explore the different ways of looking at it, linking it with other experiences and making sense in the light of the prevalent theory;

- To map out, explore and experiment with different ideas and options, envision future scenarios and approaches and capture a gap in your or another professional’s knowledge skills or attitudes and identify key actions and strategies to deal with it;

- To provide a personal record of learning and development for future use, capturing the lessons learnt and some planning on how to achieve any identified learning goals.

Conclusion

Experiential learning through reflection can play a valuable role in personal and professional development to become an effective partnership broker. It needs, however, to be grounded in some ethical and working principles to yield optimal benefits. And it needs to be sustained as a lifelong skills building activity. Done well, reflective practice has the potential to help improve the quality of our relationships and interactions with professional colleagues, and contribute to the operational effectiveness and reputation of the partnership brokering.

Would you agree? The author would be keen to hear about other experiences of reflective practice – are there any particular methodologies which have been particularly relevant and effective for partnership brokers? What kinds of challenges or barriers to reflection have been encountered and how were they addressed? This is probably contentious, but do you think there is a case for using reflective practice as a validation competency in the partnership brokering profession?

Author

After a career in the corporate sector, Surinder Hundal is now working specifically in the field of cross-sector partnerships, partnership brokering and partnership evaluation. She works as an independent accredited partnership broke and as a specialist in corporate social responsibility. She sits on the Board of the Partnership Brokers Association (PBA), the international professional association for partnership brokers. She holds a post-graduate certificate in Cross-sector Partnerships from the University of Cambridge. Surinder has worked in Asia Pacific, Europe, the USA, the Middle East and Africa, principally in telecommunications businesses such as Nokia and BT, where she led multi-faceted communications, strategy, marketing, corporate responsibility and partnership development roles. She also led policy and communications at International Business Leaders Forum. Surinder can be reached onsurinder@rippleseed.com

Footnotes

[1] Confucius (551 BC – 479 BC) Accessed from https://www.goodreads.com/author/quotes/15321.Confucius

[2] Moon, J. A. (1999). Reflection in Learning and Professional Development: Theory and Practice. London: Kogan Page: page 23

[3] Boud, D., Keogh, R., and Walker, D. (1985). Reflection: Turning Experience into Learning. London: Kogan Page: page 43

[4] Johns, C. (2004). Becoming a reflective practitioner. 2nd Ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing: page 3

[5] Ghaye, T. (2000). Into the reflective mode: bridging the stagnant moat. Reflective Practice, 1(1), 5-9.

[6] Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. How professionals think in action, London: Temple Smith.

[7] Ibid, page 68

[8] Rowling, J.K. (2004). Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire. London: Bloomsbury Publishing plc: page 518

[9] Hall, T (2016) Personal communication. Accredited Partnership Broker and Mentor at Partnership Brokers Association. Director at Thought Partners Limited www.thoughtpartners.co.nz

[10] Johns, C. (2000). Becoming a Reflective Practitioner: A Reflective and Holistic Approach to Clinical Nursing, Practice Development and Clinical Supervision. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. Page 36

[11] Tennyson R. (2008). The Imagined Conversation in Tennyson, R. and McManus, S. (2008) Talking the Walk: A Communication Manual for Partnership Practitioners. International Business Leaders Forum www.ThePartneringInitiative.org page 43

[12] General Medical Council (2015).The Good medical practice framework for appraisal and revalidation http://www.gmc-uk.org/static/documents/content/GMC_Revalidation_A4_Guidance_GMP_Framework_04.pdf ; Nursing & Midwifery Council (2015). What is revalidation? http://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/revalidation/what-is-revalidation/ ; Health and Care Professions Council (2105). Standards of Proficiency: Practitioner Psychologists. http://www.hcpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10002963SOP_Practitioner_psychologists.pdf

[13] Mann, K., Gordon, J., and MacLeod, A. (2007). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review Advances in Health Sciences Education 14(4). 595–621 DOI 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 [Accessed 22 December 2015]

[14] Greeley, E., Accredited Partnership Broker, St. John’s, Newfoundland Canada Partnership Broker with the Community Career & Employment Partnership www.ccepp.ca; Also on https://elaynegreeley.wordpress.com

[15] Karkabi, K., Wald, H.S., and Cohen-Castel, O. (2013) The use of abstract paintings and narratives to foster reflective capacity in medical educators: a multinational faculty development workshop. Medical Humanities. Institute of Medical Ethics & British Medical Journal. doi:10.1136/medhum-2013-010378 http://mh.bmj.com/content/early/2013/11/22/medhum-2013-010378.full

[16] Aull (2012) What the Literature, Arts, and Medicine Database is and How to Use it. Resource for a New Paradigm for Training Doctors. http://www.med.nyu.edu/medicine/medhumanities/about-the-literature-arts-and-medicine-database

[17] Strauss, M. (2016) The Log of Pi in One Word. Accessed from New York University School of Medicine (2016) Literature, Arts, Medicine Database (LITMED) (http://medhum.med.nyu.edu/about)

[18] Good reviews of the models can be found in Mann, K., Gordon, J., and MacLeod, A. (2007). Reflection and reflective practice in health professions education: a systematic review Advances in Health Sciences Education 14(4). 595–621 DOI 10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 http://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10459-007-9090-2 as well as in Ghaye, T. and Lillyman, S. (2008). Learning Journals and Critical Incidents: Reflective Practice for Health Care Professionals. Quay Books/Mark Allen Publishing Ltd

[19] Gibbs, G (1988). Learning by doing: a guide to teaching and learning methods. Oxford: Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic. Monograph online reproduced by Geography Discipline Network 2001 http://www2.glos.ac.uk/gdn/gibbs/index.htm

[20] Kabat-Zinn, J. (2012) Mindfulness for Beginners: Reclaiming the Present Moment-and Your Life. Sounds True Inc; Har/Com edition

[21] Tennyson (2008) ibid

[22] Dieleman, R. Accredited Partnership Broker, The Netherlands ritadieleman@outlook.com

[23] Bassot, B. (2013). The Reflective Journal. Palgrave Macmillan