Abstract: This paper examines strategies for partnership brokering among small, fast-moving organisations where partnerships are crucial but the broker is required to skip or streamline some of the steps in the Partnering Cycle in order to fit the pace of the partnership’s work. In contrast with complex sustainable and community development examples, our partnerships at Digital Promise often involve fewer partners with more obvious commonalities, and a shorter timeline (perhaps a few months as opposed to years). Nevertheless, careful brokering is imperative. The Partnering Cycle I developed as an internal broker for Digital Promise focuses on the two “inflection points” of brokering where we must be most careful while still moving quickly: the scoping and building phase, and the reviewing and revising phase. In this paper, I expand on these inflection points, and the tools and strategies I developed, aiming to provide a perspective on and resources for partnership brokering in fast-moving and changing environments.

Brokering in fast-moving partnerships: a Digital Promise case study

In a twist of fate and timing, I found myself at the Partnership Brokers Level 1 training course in Hong Kong in November 2013 only two weeks after I’d started a job at Digital Promise. With my peers in the training, I struggled to explain the intricacies of Digital Promise’s origins (authorised by the U.S. Congress, but nonpartisan and not funded by government). I stumbled through explanations of how we worked to fulfill our mission to spur innovation in education to improve the opportunity to learn for all Americans.

Nevertheless, I dove into the brokering training ready to absorb as much as I could. I already knew that Digital Promise operated “at the intersections,” as we say, creating opportunities for educators, researchers, and entrepreneurs to work together for the benefit of students. When these groups work in silos, as they so often do, education stagnates. Digital Promise’s work to ensure a free-flowing ecosystem of all these groups is deeply rooted in partnerships.

The Level 1 training helped me to develop a sense for the skills and sensibilities necessary to build and manage collaborative partnerships, some of which I had begun to develop organically and others that I knew I would need to practice. A few months after the training, I moved into a role managing Digital Promise’s Corporate Partner Program. Soon after, I began to develop a global initiative whose strategy rested upon partnerships with complementary organisations around the world. When I started my PBAS Level 2 mentorship[1] (ie for footnote 1), I also began to take a closer look at all the partnerships in which Digital Promise engaged, and an insight that began as a tentative observation gained strength. That insight: the Partnering Cycle[2] (ie for footnote 1) that was so helpful in the Level 1 training was not making as much sense in the context of Digital Promise partnerships.

Digital Promise Case Study

An example will help illuminate this insight. One of our most collaborative partnerships, and one that produces a highly successful program, is one that began in a rush. This was less by choice than by necessity: the program that our two organisations would offer over 6 months needed to be kicked off within the first month in order to align well with the school calendar. Our organisations had frequently crossed paths, working in many of the same networks, and we felt familiar with each other’s work and goals. We started work on the project before partners actually agreed on an MOU, assuming that we could come to an understanding and the MOU would be acceptable. Even when the first draft of the MOU produced misunderstandings, both partners felt so bought in to the process that we quickly edited most of what needed to be changed, signed, and breathed a sigh of relief, thinking we had solved the issue.

The work of the partnership continued, occasionally with bumps, which we barely had a chance to address before forging ahead. We closed the project thrilled with our success and the impact we had made together. Only then did we realize that both partners had misunderstood one important section of the MOU, and we found ourselves working out that common understanding far later than we would have liked. Nevertheless, both sides decided to continue the partnership and run the program again. Despite the bumps in the road the first time around, we knew that many of our organisations’ goals were well aligned, we had developed effective strategies for communication, and we agreed about areas in which we needed to improve.

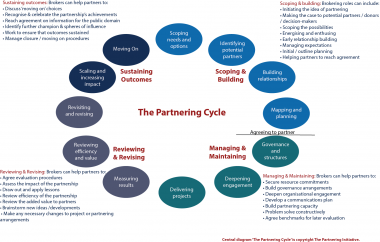

As I watched this story unfold as an internal broker, I often found the process totally out of sync with the Partnering Cycle that I’d worked with during my Level 1 training (see Figure 1). As someone who appreciates process, I valued the Cycle for how thoroughly and carefully it presented each piece of the brokering process. The examples we worked with during the training were extremely complex and sometimes highly volatile. For instance, I remember facilitating a fictional MOU negotiation between a company, a local community, a government, and an NGO regarding the construction of a mine in the community. I found that the cycle was necessary to measure and inform our deliberate progress.

In the example I just gave from Digital Promise, we whizzed by the first few steps of the cycle in a few days. We never considered other organisations to partner with for this project, and governance and structures were barely touched upon before we began delivering pieces of the project. As the project gained momentum, as a broker it was almost impossible for me to identify which step we were at in the cycle – we constantly seemed to be at multiple steps at once, and in the confusion, we brushed by certain issues that we should have paused to solve.

None of this is to say that the Partnering Cycle is wrong, or unnecessary. Neither is it to say that the Digital Promise partnership I described was so perfect and easy that the cycle was irrelevant. Rather, the Cycle is of utmost relevance for many kinds of complex partnerships, like the mining example from my Level 1 training. And my Digital Promise experience, despite the high alignment of partners’ goals and a positive end result, had its fair share of misunderstandings and cross-sector challenges. The point here is that some kind of process or cycle is necessary, but the Partnering Cycle felt excessively complicated for the kind of partnerships that Digital Promise engages in. Our partnerships are fast-moving and often operate over a much shorter timeframe. Partners may work in different sectors but often cross paths in the education technology field, so arriving at shared goals and values can often be a rapid process. I began rethinking the Cycle so that it addressed the most critical areas that we struggled with in Digital Promise partnerships, but accommodated the pace and scope of our work.

A Partnering Cycle for a Particular Context

As partnership brokers, we are supported by the resources and experience of our mentors, colleagues, and professional association. Our field is an ever-evolving one in which we are united by core principles of practice, but constantly tweak and refine our approaches in different situations. In my work I am grateful to be part of a group of professionals committed to driving the field forward, building on each other’s work.

During my Level 2 mentorship, recording and reflecting on my partnership experiences helped me to identify the most critical parts of the Partnering Cycle for our context and produce a modified framework that would help my Digital Promise colleagues better build and manage the partnerships in their projects. I share it here both as a resource for others who manage fast-paced, shorter term, and highly aligned partnerships, and in hopes that it might spur a conversation about how the cycle of partnership brokering changes (or not) depending on context.

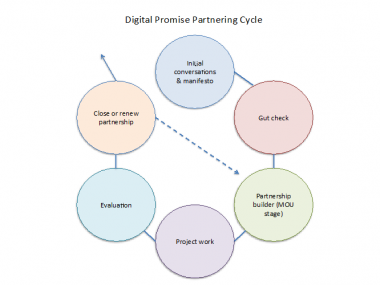

Figure 2: An overview of the Digital Promise Partnering Cycle. The first three steps, along with the Evaluation, are accompanied by documents or worksheets of one page or less.

All partnerships begin with initial conversations, when partners explore goals and how each might contribute to a common project. For Digital Promise, it is important during this phase that we clearly share our vision for partnerships upfront. The manifesto document I created describes how the partnerships we engage in are collaborative and action-oriented, with shared goals and risks. The document also includes three essential principles that resonated with me from the PBAS Level 1 materials. In successful partnerships, we aim for equity between partners to result in respect, transparency to result in trust, and mutual benefit to result in engagement in the project. Whether this manifesto is shared with a potential partner as a document or simply discussed together, it needs to be put forward in initial conversations to give a partner an idea of our partnership philosophy and invite them to share theirs.

From these conversations, the cycle moves to an internal “gut check.” Often the partnerships we build need to start working and producing results very quickly. Before getting too invested, though, we need to stop and ask ourselves a few key questions. For example: is there a clear value proposition for us in working with this partner? Are the partner’s individual goals and interests compatible with the shared goals of the partnership? Does the partner already work in a way that aligns with our mission and values? Do both partners have the capacity to do the work that’s needed? The intention is that answering these questions will provoke a kind of gut reaction – whether “Yes, let’s go!” or “We need to examine this more and move carefully” or “Maybe this isn’t a great idea.”

If the gut check leads us to move ahead, the next step is to discuss and complete a 1-page framework to clearly define the partnership. If initial conversations have been successful, this document should be easy to complete, and could serve either as a brainstorm for an official MOU, or the MOU itself. This document has three core sections. In the first, partners outline the scope of the shared work of the partnership: goals, timing, and definitions of success and failure. The second part is aimed at understanding individual partners: what is each partner’s value proposition and risk from an individual standpoint? Some items may be common among partners, but the most important to list are those that are unique to one partner so that everyone can be aware of this motivation. Finally, the third section details how the partnership will work: how decisions are made, key activities and ownership, resources and contributors, and common principles that will guide the partnership’s work.

Then comes the work of the partnership, if it hasn’t begun already. I noticed in my brokering that the sticky parts of Digital Promise partnerships tend to be points of inflection: deciding whether or not (and how) to partner, and later, evaluating an option to partner again or to move on. In collaborative work, complexities naturally arise, but my hypothesis is that if we better consider and define the partnership at the outset, the collaborative work is likely to move more smoothly, and if conflict arises it might be solved by returning to some of the key questions we discussed and agreements we made at the beginning of the partnership. Better that we face conflict once we know we’ve asked the right questions than when we thought those questions didn’t need to be asked.

The final step in the cycle is evaluation. The document for this step echoes the Partnership Manifesto almost verbatim. Partners reflect on how the partnership succeeded in embodying the foundational principles in the manifesto, whether partnership goals were met, and which aspects of the partnership helped or hindered the achievement of those goals. This document provides a clear opportunity for partners to pause and evaluate their common work before moving forward or closing the partnership.

My goal with this modified cycle is not to claim that partnership brokering is easy, requiring nothing more than filling out some documents. Nor does it throw out the core principles of the Partnering Cycle. Rather, I aimed to distill the Cycle down to something that fits the pace and style of our work, providing my colleagues with concrete steps and clearly worded questions that would help us quickly build and get started on a partnership without sacrificing the integrity of the partnership brokering process.

Author

Chelsea Waite directs the development of Digital Promise Global, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to spurring innovation in education to increase the opportunity to learn. Previously, she served as a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant and English program coordinator in Brazil, where she also founded educational initiatives designed to increase access to English classes and international study opportunities. Chelsea is accredited by the Partnership Brokers Association, has considerable experience with program management, and is an advocate for global competence as an essential part of a well rounded education. She teaches capoeira, a Brazilian martial art, and graduated with a degree in history from Brown University.

Chelsea Waite directs the development of Digital Promise Global, a nonprofit organisation dedicated to spurring innovation in education to increase the opportunity to learn. Previously, she served as a Fulbright English Teaching Assistant and English program coordinator in Brazil, where she also founded educational initiatives designed to increase access to English classes and international study opportunities. Chelsea is accredited by the Partnership Brokers Association, has considerable experience with program management, and is an advocate for global competence as an essential part of a well rounded education. She teaches capoeira, a Brazilian martial art, and graduated with a degree in history from Brown University.

Footnotes

[1] Formal professional accreditation to the Partnership Brokers Accreditation Scheme (PBAS) is achieved through successful completion of a 3.5 month period of (long distance) mentored professional practice. Accreditation is the key element in the move towards creating the new profession of ‘partnership broker.’ More info on https://partnershipbrokers.org/w/training/level-2

[2] The Partnering Cycle developed at The Partnering Initiative is a schematic framework showing the progression of a typical partnership over time.