Abstract: Knowing when to seek assistance and engage external support in a partnership is not easy. Just how this support may best be utilised and work with an organisation’s internal brokers can be challenging. In this case study, we explore how a combination of external and internal brokering is working to facilitate an innovative partnership between an important remote Indigenous art centre and a leading University in Australia. In 2011, the Gija Community in North Western Australia and the Centre for Cultural Arts Conservation within the University of Melbourne began a relationship, initially to restore art works damaged by major flooding. While the relationship developed informally, there was a desire to expand the partnership to achieve a greater impact. An external broker was engaged to work with the internal brokering unit to design a suitable intervention to move the partnership forward.

From External to Internal: Brokering a 2 Way Learning Partnership

Authors: Ian Dixon (the external broker), Mark Nodea (the community-based partnership manager) and Jacob Workman (the internal broker)

“All the art was gone except the works of the old people.” – Mark Nodea

In March of 2011, a devastating flood washed over the remote East Kimberley community of Warmun, Western Australia. Water swept through the local art gallery and studio, gathering up and damaging much of the community’s treasured Indigenous art collection. By the time the river subsided, most of the modern artwork had been washed away.

Much of the Community Collection – cultural treasures created by the first generation of Warmun painters including Jack Britten, Rover Thomas, Hector Jandany, George Mung Mung, Rusty Peters and Queenie McKenzie – was housed in an internal room of the Art Centre. While these artworks were not lost, they were severely damaged by water, mud and silt. By the time the room was accessible, mould covered many of the pieces.

Community elders, historians and artists shouldered the pain of the devastating aftermath, but like the diluvian flood of legend, the receding waters created fertile ground: a partnership was forming.

Warmun Art Centre is the cultural and community hub of the Gija people. Its artworks and artefacts serve as a repository for knowledge; they record and tell the stories of Ngarrangkarni, the Gija Dreaming. Since its creation, the precious Community Collection has been used by elders to teach younger generations. The works document the traditions of the Gija people, from stories and histories right down to the ochre and artistic materials used in their production. They are of immeasurable significance.

Argyle Diamond mine staff assisting with the evacuation of artwork from Warmun. Photo courtesy of the Warmun Art Centre

In the days which followed the flood, Warmun artists took swift steps to save the collection. A call was made through ANKAAA (Arnhem, Northern, Kimberley Aboriginal Artists Association) to the University of Melbourne’s art conservation specialists, who despatched a senior art conservator from the Centre for Cultural Materials Conservation (CCMC) to begin urgent stabilisation of the material. Local mining and logistics firms, Argyle Diamonds and Toll Holdings, contributed to the efforts by providing helicopters and refrigerated transport vehicles to move the artwork to Kununurra and eventually down to Melbourne. CCMC staff and students spent the next two years working with the Warmun Art Centre (WAC) and Gija artists to preserve and restore the collection. The artworks returned to Warmun – fully cleaned, restored and documented – in June of 2013.

“It’s a big project, you know? Plenty big.” – Mark Nodea

Although the partnership was forged out of necessity – a seemingly transactional relationship (sprinkled with elements of sponsorship as well) between the Art Centre and the University – it slowly evolved. CCMC and WAC staff maintained regular contact throughout the process. Gija artists flew to Melbourne to advise on the painting techniques they use and to learn about restoration. Likewise, conservators and students visited Warmun to learn first-hand the techniques and stories that produced the stunning works. Relationships grew stronger with every interaction. The partners began discussing “what’s next?”.

The Community Collection was initially intended to be a resource for teaching Gija youth about their culture and history. It conveys multidisciplinary lessons: language, Ngarrangkarni stories, ritual practices, skin system relationships and history. Similarly, the collection provided active learning for CCMC students, who spent two years working on the artwork and learning the craft of conservation. Why, however, should the rest of the lessons – 40,000 years of Gija knowledge – remain untapped? The partners recognised an opportunity to use the Community Collection to teach Gija knowledge to University of Melbourne students, some 3,500 kilometres from Warmun.

At this stage, the partnership faced many considerations, complexities, hurdles and speed humps. Fortunately, the partners brought with them a wealth of experience and cross-cultural awareness. From the outset, reciprocity was paramount; Gija knowledge and expertise was acknowledged as equally valid to traditional Western empirical understanding. Proposed partnership structures reflected this ideal: Gija elders were viewed as professors, artists as lecturers, partnership managers were accountable to one another, with each remunerated accordingly.

The partnership, on paper and in theory, was poised for success. The two-way knowledge approach was novel, if not revolutionary; certainly a stark divergence from the traditional higher education knowledge paradigm. The partners had by now established incredibly strong relationships and goodwill. They thoroughly and sincerely enjoyed working with and learning from one another. Together, they had built a shared understanding of the opportunities ahead and had an idea of what a successful partnership looked like.

But how were they going to operationalise it? Get buy-in and communicate it? How were the partners going to embed the partnership within their communities and organisations, and who, importantly, was going to do it?

“It’s a good idea, but will everyone accept it?” – Mark Nodea

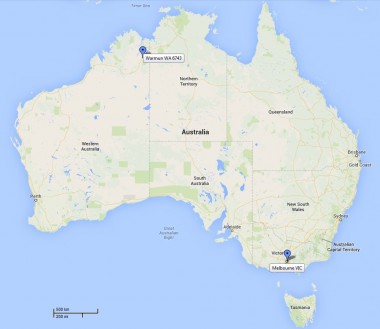

The Warmun community is, by almost any standard, incredibly remote. It lies some 200 kilometres from the nearest population centre and has approximately 600 residents. Despite its location and size, its art and artists are internationally exhibited and world-renowned.

The University of Melbourne is one of Australia’s premier research institutes. Its main campus comprises several blocks in the heart of Melbourne. The University employs over 7,000 individuals and has a student body of 40,000. The Melbourne Engagement and Partnerships Office (MEPO) is a small team of partnership consultants and support staff who assist faculties in partnership development.

Each year the University of Melbourne recognises examples of outstanding engagement through the provision of excellence grants. The WAC-CCMC partnership was awarded such a grant in late 2012. MEPO’s director (a PBA alumna) approached the director of CCMC and offered to support the partnership. It was through this connection that MEPO was introduced to the partnership.

In June 2013, shortly after the Community Collection was returned to Warmun, the MEPO director accompanied the CCMC team on a visit to the Art Centre. The trip corresponded with a gathering of Gija elders and community leaders at a traditional meeting ground on Violet Valley Station, where they met to discuss the direction of the partnership. Although all of the immediate partners – those directly involved in the restoration work – got along incredibly well, some community members felt that the University was prone to too much jarak jarak (talking) without much action. The WAC manager also voiced concern about how a larger partnership might impact the community.

Ultimately, the elders decided to support pursuing the next stage of the partnership. The MEPO director suggested to the partnership managers that the office facilitate a workshop in Warmun later that year with the aims of advancing the partnership. However, the Gija decided that holding it in Melbourne was preferable, so that their delegation might learn more about how the University operates.

Back in Melbourne, a MEPO partnership consultant was asked to organise the workshop. Consultations with stakeholders across the University revealed latent complexities: the Legal team (the University has more Legal team members than WAC has staff) were not entirely comfortable with the innovative approach – even generic terms such as “partner” and “partnership” carry legal weight in Victoria; the highly bureaucratic structure of the University created ambiguity about “ownership” of the partnership; CCMC’s parent department was anxious about the reciprocal staffing proposal; the University’s institute for Indigenous development had a vested interest in ensuring the partnership’s success; and the advancement team was tracking the philanthropic support of a few key donors.

Navigating the internal politics as an internal broker already presented enough of a challenge. The “voice” of each of the internal stakeholders needed representation in workshop discussions. The partnership consultant was also acutely aware of the potential cultural sensitivities and nuances involved in partnering with an Indigenous community. Despite considerable facilitation experience, the consultant had never conducted a workshop with Indigenous participants. Furthermore, although the workshop was to take place in Melbourne, the partnership was built on the tenets of equality and reciprocity. It was imperative that all participants felt equally represented, comfortable to transparently discuss desired outcomes and concerns.

Everyone wanted a meaningful and effective workshop. The primary facilitator needed to instil confidence in the participants; someone who provided an air of legitimacy, authority and impartiality. The MEPO consultant sought the services of an independent partnership broker with extensive Indigenous experience.

“And he said it would be hard, you know?” – Mark Nodea

Enter the external broker, Ian Dixon. He was approached by Jacob Workman, the partnership consultant from the University of Melbourne, with the initial brief to provide some partnering skills training to core members of the CCMC and the WAC partnership.

Ian’s first task was to gain a thorough understanding of the history of the relationship, partnering activities undertaken to date and key challenges the partners were facing. He wanted to get below the surface and really understand what had transpired between the partners since they started working together back in 2011.

After several more discussions and briefings from Jake and members of the CCMC, Ian discovered:

- The partnership had focussed on some specific activities due to the urgency of restoration needed at the time;

- Considerable goodwill existed among the core partnership group, with much time and effort spent on establishing and nurturing trust and mutual respect;

- Although key partnership principles were articulated and understood, little formal documentation had been created around the partnership. It was unclear what, if any, underlying issues between the partners might exist;

- There had been discussions about taking the partnership to another level, but the partners were unsure how to do this;

- The remoteness of the Warmun Community presented many challenges but there had been a strong effort to maintain communications through regular Skype calls and a number of reciprocal visits by core members of the partnership.

In reviewing the partnering stages, one cycle of partnering (the restoration of significant artworks) had been completed. To take the partnership to a new level as envisaged by the partners would require revisiting the scoping and building phase and exploring key questions around the new purpose and objectives. It was also evident that both partners sought clarity around a number of areas and wanted this formalised in a partnering agreement.

The outcome of these discussions and briefings was the development of a workshop structure that would both provide some knowledge and skilling around partnering as well as produce a draft partnering agreement. In conjunction with CCMC representatives and the internal broker, Ian set about designing the scaffolding of a two-day workshop that aimed to achieve these objectives. This planning was challenging on account of the tight timelines and the fact that liaison with the Warmun-based partners occurred indirectly through the University.

“You build trust by listening.” – Mark Nodea

One of Ian’s concerns prior to the workshop was the need to meet and engage with the WAC representatives, as all the planning discussions had been through the internal broker and the CCMC members. To confirm that everyone was comfortable with him as a facilitator and the workshop structure, Ian arranged a pre-meeting on the afternoon prior to the workshop to informally meet the partners and to run through the process for the next day. Here Ian first met Mark Nodea – a celebrated Gija artist, chairman of the Warmun Art Centre and the community-based partnership manager.

It became clear that other important outcomes of the workshop were the creation of an ‘action plan’ of activities for the partnership and ensuring that everyone around the table shared an understanding of the current status and future direction of the partnership. This would enable members of the partnership to meet key stakeholders and benefactors after the workshop to communicate the partnership story.

The tasks set for the workshop were challenging given the timeframe, but with limited flexibility to extend the workshop, an intense schedule was inevitable. Thankfully, these partners were no strangers to hard work.

“Without Ian, we would still be talking today.” – Mark Nodea

With this in mind, the scaffolding was fleshed out. The internal and external brokers worked together to design a workshop that, over one and a half days, intended to: impart some knowledge – drawing heavily on Ian’s past experience – of cross-sector partnering frameworks and models that could assist WAC and CCMC in working together even more effectively in the future; explore the current status of the partnership and unearth any key issues that needed to be addressed and resolved before they could move on; ensure that the partners had some substantive outcomes by way of an action plan and draft partnering agreement; develop a sense of shared ownership for this action plan and partnering agreement; and, support the internal broker and gradually transition through the workshop from the external to the internal broker regarding ongoing support.

Day one of the workshop saw the facilitation approach of ‘fanning out’, enabling exploration of issues, transfer of partnering knowledge, surfacing of underlying issues and an opportunity to clarify the future direction of the partnership. Ian was pleased to learn that a draft partnering agreement (based on a template provided by MEPO to the partnership managers) had been started by several members but had not been finished or formalised. This provided a useful framework and starting point to move forward and to recognise some of the previous work. Considerable debrief, data capture and further preparation on behalf of both the internal and external brokers – including a flurry of calls and emails well into the evening – allowed the partners to start the next morning with a head of steam. As Mark pointed out, day one planted the seed.

Ian’s approach on the second day changed to focus on resolution and agreement and to ensure that the partners arrived at desired outcomes – growing the tree. Ian also started to step back and enable the internal broker to lead some sessions on action planning which supported the transitioning approach from external to internal broker. By lunch on day two, the partners had co-created a comprehensive partnering agreement draft that both sides were excited to share with their wider stakeholders. This was an important aspect for the partners; the documentation displayed solid evidence for others that the partnership was on track and has a positive future.

The workshop went extremely well, if not quickly, and most objectives were achieved in the one and half days set aside. The workshop was followed by an impressive and very positive briefing session where Mark shared the outcomes of the workshop and provided a vision of the future to a diverse group of stakeholders.

“The organising side and the understanding side.” – Mark Nodea

The workshop provided an opportunity for two strangers working in similar fields to come together to create and deliver an effective partnership intervention. As a case study in internal / external broker, a number of professional lessons surfaced – some new, others reinforcing existing practices:

As an external broker being asked to come in for a specific intervention such as a workshop or training session, it is critical to get as much understanding as possible of not only what has taken place but how the partners have related to each other. The time spent on this aspect is vitally important, and brokers often underestimate this activity.

It was also important to stress the independence of the external broker as a facilitator at the pre-meeting, especially given that all of the preliminary discussions had taken place with University staff. Ian wanted the Warmun community members to feel that he was working equally to achieve a good outcome for both partners. This was important for his integrity as an external broker and for the transparency of the process. The issue is a consistent Janus face confronting internal brokering units, but illustrates the value that external brokers can bring. When Ian asked Mark if he felt “side-by-side” with the University, Mark affirmed that he felt they had “come together to negotiate one work, Gija people together with the Uni.”

From past Indigenous workshops, Ian was conscious of cultural differences and possible challenges in language, he deliberately planned to only go as fast as the partners would allow. He soon realised that there was a very good relationship between the partners and high levels of trust, which enabled them to achieve what they did in the tight timeframe. Upon reflection, however, even the best intentions are no match for impending deadlines, and more time for thinking, formulating and responding would have been desirable. Allowing for adequate silence will usually produce the best results. This does illustrate a difficulty of external brokers – they are largely restricted to work within the confines set out by the partners, or in this case, the internal broker.

It was pleasing and relieving, though, to see that in this environment the partners were prepared to put underlying issues out on the table; this came even more readily on day two, after a productive and intense first session. Although not all brokers are fortunate to work with partners exhibiting this level of comfortability with each other, building on successes will usually assist with reducing barriers to communication.

Ian was aware that he was being asked to come in as an external broker for just this one session and that ongoing support would be available through the MEPO internal brokering unit. For this reason he was keen to actively transition from external to internal throughout the workshop. This was achieved by actively seeking and taking opportunities to co-facilitate, with Ian taking the lead on day one and then transitioning to the internal broker facilitating more of the sessions on day two. The change of his facilitation style was quite deliberate and designed to open up discussion and surface issues on the first day and to focus on key outstanding issues on day two.

This seemed to work well, and although it may have seemed a little directive on day two, it helped to reach the desired outcome. The partners appeared comfortable with this approach, as Ian had established his credibility as a facilitator at that point. This allowed for Jake to facilitate in a relatively ‘softer’ and more collaborative way.

Of course, documentation matters. A critical aspect was taking the notes from the first day and developing a draft partnering agreement and action plan for presentation back to the partners on the morning of day two. This work was undertaken jointly by the internal and external broker overnight and moved the process on very quickly on day two, enabling partners to focus on resolving the outstanding issues.

“We gotta get the Gija connected more strongly with the University…” Mark Nodea

The workshop also provided a unique learning opportunity for the internal broker, who was tasked with continuing to support the partnership henceforth. Although Jake had met some of the Gija – including Mark – at various junctures over the past year, he had not yet visited ‘on country’ and was not yet actively used to support the partnership. Appropriate participation in and facilitation of the workshop would underpin his ability to effectively do so in the future. Importantly, the tenet that partnership brokers must have no ego applied here.

The internal broker needed to be comfortable taking a backseat, listening actively, ‘letting go’ and allowing the external broker to do what he was brought in to do. Jake supported Ian both behind the scenes and in the workshop, but on day one, he was largely a silent partner. These first sessions also reinforced the value of scribing – those critical skills of observation, learning, identifying themes and synthesis proved invaluable. All of this served to build the relationship with all of the participants, which in turn helped establish trust.

Jake worked closely with Ian to ensure that key materials and messages were ready for next session. Armed with this preparation, he transitioned to a more active facilitation role on day two, culminating in a subtle but distinct ‘handover’ from external broker to internal broker. This process was absolutely critical for establishing legitimacy – almost as if it was earned and granted.

The intervention was a success on other levels as well. One of the key challenges identified by the internal broker was managing the expectations of multiple internal stakeholders at the University. The workshop, and especially Mark’s presentation of the outcomes, expanded the University community familiar with the partnership, its objectives and its future. It also served to build the partnership skills of the key partners, introducing a framework that WAC and CCMC could jointly refer to and revisit. Finally, the workshop revealed, as identified by Mark, that that WAC can and should bring their expertise to bear, particularly around educating University stakeholders about the needs of Indigenous people in future workshops – providing adequate time and space for opportunities for reflection and discussion in their own way and on their own timeline. These outcomes will undoubtedly make the partnership even more resilient and self-sustaining

“… And we gotta keep on moving Melbourne into the community.” – Mark Nodea

The WAC-CCMC partnership workshop was an interesting, exciting, valuable and rewarding activity for both the internal and external broker. It really did illustrate the value of external brokers – particularly in partnerships involving large organisations or those requiring specific expertise. In this instance, both were present. Internal brokering units face difficult juggling acts, often subject to perceptions of prejudice or a lack of independence, particularly in bureaucratic and ‘siloed’ organisations. But this case also highlights the value that they can add by acting as an ‘external’ internal broker. With the requisite legitimacy, authority and expertise, they can design and deliver effective interventions across any range of partnerships.

Ultimately, Ian delivered on all accounts – in terms of both the workshop and in supporting the internal broker. But as an external broker, his involvement in the partnership was short-lived. Jake is now tasked with supporting the WAC-CCMC partnership as an internal broker for CCMC and the University, but also as a resource for Warmun, should they need him.

Mark has been busily sharing the partnering agreement and the action plan with the Gija people, the Warmun Art Centre and the wider Warmun community. Similarly, the CCMC team have been working tirelessly to secure the necessary support and buy-in across the University. Things appear to have come together – a senior University of Melbourne delegation is scheduled to travel to Warmun for a formal partnering agreement signing ceremony in April.

Of course, the partners themselves, WAC and CCMC staff, recognise that there is still much work to do and acknowledge that most of it will fall to them. Recall, however, that this mob is no stranger to hard work. This innovative and ambitious partnership is in the right hands and has a bright future. As Mark said, “We need to trust each other… we gotta stick on what we say. This is the right way to do it.”

Authors

Ian Dixon is an internationally recognised Partnership Broker who is at the leading edge of cross-sector partnering development and practice. As Principal for Dixon Partnering Solutions and an expert in this field, he is sought after as a strategic adviser, keynote speaker, coach and mentor. You can contact Ian via his website: www.iandixon.com.au.

Ian Dixon is an internationally recognised Partnership Broker who is at the leading edge of cross-sector partnering development and practice. As Principal for Dixon Partnering Solutions and an expert in this field, he is sought after as a strategic adviser, keynote speaker, coach and mentor. You can contact Ian via his website: www.iandixon.com.au.

Mark Nodea is a celebrated Gija artist and current Chairman of the Warmun Art Centre. Drawing on his personal knowledge of walking in two worlds of traditional and contemporary life, Mark brings a wealth of expertise and a unique perspective to this partnership and all that he does. You can learn more about Mark through the Warmun Art Centre: www.warmunart.com.au.

Mark Nodea is a celebrated Gija artist and current Chairman of the Warmun Art Centre. Drawing on his personal knowledge of walking in two worlds of traditional and contemporary life, Mark brings a wealth of expertise and a unique perspective to this partnership and all that he does. You can learn more about Mark through the Warmun Art Centre: www.warmunart.com.au.

Jacob Workman is a partnership consultant for the Melbourne Engagement & Partnerships Office at the University of Melbourne. His current role draws on his extensive experience in the corporate and higher education sectors and provides a unique platform to combine his commercial, academic and public-speaking backgrounds with his unquenchable thirst for knowledge. You can contact Jacob via the MEPO website: www.mepo.unimelb.edu.au.

Jacob Workman is a partnership consultant for the Melbourne Engagement & Partnerships Office at the University of Melbourne. His current role draws on his extensive experience in the corporate and higher education sectors and provides a unique platform to combine his commercial, academic and public-speaking backgrounds with his unquenchable thirst for knowledge. You can contact Jacob via the MEPO website: www.mepo.unimelb.edu.au.