Abstract: There is increasing interest in generating substantive evidence of the impact that brokered partnerships have on the outcomes of multi-stakeholder partnerships. Evaluations of partnership broker approaches and indeed of the performance of individual brokers themselves contribute to such evidence. But what methodologies can be used to conduct such evaluations? Drawing from her experience of conducting an evaluation of Oxfam’s partnership broker approach in Jamaica, the author suggests some key building blocks which can be used to develop a customised evaluation process to assess a brokered partnership and the performance of the broker(s) facilitating it.

Evaluating Partnership Broker Approach: A methodological perspective

Partnership brokers are constantly building their own knowledge and contributing to the wider understanding of partnership brokering as a dynamic and evolving field. Every partnership we are involved with is an opportunity for experiential learning and indeed for developing new approaches and methodologies on how we could do our work better and help partners to optimise their collaborative benefits.

In 2011, Oxfam commissioned the Partnership Brokers Association (PBA) to evaluate its partnership broker approach in Jamaica. This evaluation I carried out on behalf of the PBA provided me with a unique opportunity to design and deliver a customised brokering evaluation approach. In this article, I have drawn on that experience to suggest some building blocks, which could be used to evaluate a partnership broker approach and to assess a broker’s performance.

Evaluating a partnership broker approach

In 2009, Oxfam had invested in a pilot project to implement a partnership broker approach in Jamaica. Its main purpose was to replicate a project in its market-based rural livelihoods programme, for improving market access for micro and small-scale rural agricultural producers to tourism product and service providers; and to trial the broker approach as part of a regional exit strategy. Oxfam would act as a ‘broker’, taking on the role of a facilitator, rather than participate as an implementing organization. It appointed a Jamaican national and a Partnership Brokers Association Level 1 graduate as its full-time partnership broker.

In the terms of reference for the evaluation, Oxfam identified its scope, setting out some objectives covering both the partnership project and the broker’s role and performance. Understandably, it did not express any preferences for or specify any particular evaluation methodologies.

Typically, in assessing a partnership broker approach, we may have three purposes: (a) to assess the efficiency and effectiveness of the particular approach adopted; (b) to understand the impact of the partnership broker approach and its value to the individual partner organisations and to the communities involved with the projects; and (c) to evaluate the partnership broker approach as a paradigm to be compared with other options for delivering development projects.

Inevitably, this means examining the nature, quality and efficacy of the brokering interventions in the partnering cycle – in terms of both the performance of the broker (or brokers) and the processes and practices adopted. The evaluation methodology selected has to provide data on the broker and the brokering process.

As a prerequisite to the selection of the evaluation methodology, I have found it helpful to do the following tasks:

- Understanding and defining the partnership context for the evaluation

- Defining and agreeing a clear scope for the evaluation

- Clarifying the evaluation language

- Defining a set of indicators for the evaluation

Starting from the basis that the broker approach is informed by the partnership’s purpose, its projects, its typology and structure and role of the constituent partners, an important first step in any evaluation is to establish the context for the broker approach.

For instance, in the case of the Oxfam project , there were different types of partnerships (focusing on purpose) and partnership ‘institutions’ (focusing on structure) within the programme. I identified four types of partnership institutions [1] – intermediary, local alliance, dispersed and temporary structures – performing respective brokering, social business, resourcing and technical roles. This configuration was the context for the broker approach and presented the types and sources of data available; influencing my subsequent work on the data collection techniques and materials I needed to support the evaluation.

Setting and agreeing the boundaries for the assessment in the form of a set of clearly articulated objectives and assessment criteria ensures there is no subsequent ‘mission creep, misunderstanding or ambiguity about the purpose or the scope of the evaluation.

Oxfam had identified this scope for me in the terms of reference for the evaluation; the objectives were to (a) evaluate the effectiveness / level of success of the partnership broker approach; (b) recommend improvements to the partnership broker approach; (c) evaluate the role of the partnership broker; and (d) measure and evaluate the cost effectiveness of the partnership broker approach versus the country programme approach it had used in other local markets.

Objectives set for an evaluation typically contain terms such ‘effectiveness’, ‘success’, ‘impact’, ‘outcomes’, ‘value-add’. When we clarify these terms in the context of the evaluation, people whose projects or personal performance is being reviewed are able to use a ‘common language’. Failure to clarify the terms may mean that they and the evaluator end up speaking at cross-purposes from very different perspectives, positions and interests. Taking time to define and qualify the terms used in the assessment also helps the assessor to apply a coherent and consistent approach and seek comparable data.

In the Oxfam evaluation, I characterised ‘effectiveness’ and ‘value-add/benefits’ of the partnership broker approach in the following way:

- The partnership broker approach is doing what it set out to do: the partnership and the projects which are the subject of the evaluation have achieved or are on target to achieve their original goals;

- The partnerships involved have had some ‘added value’ to date in which individual partners have gained benefits from Oxfam’s brokering and facilitation roles;

- The partnership broker approach is having a wider impact, drawing some recognition of achievement from the agricultural sector, the tourism sector, the government and other key stakeholders;

- The partnership broker approach is encouraging sustainable and self-managing solutions within its approach and has a coherent and cohesive strategy for supporting long-term development beyond the ‘start-up’ phases.

Such descriptions are useful in setting out the overall direction and purpose for the evaluation, but they then need to be underpinned with some specific indicators and criteria to be assessed. Efficient terms of reference for the evaluation – such as provided by Oxfam – will already prescribe a set of indicators and sources of data which could be used in the assessment. If they have not been defined substantively, the evaluator needs to agree a set of measures for each of the objectives for the evaluation with the person who has commissioned the evaluation.

Once the measures, the context of the partnership, the scope of the evaluation and its objectives are established, the task of selecting a methodology can begin. In most cases, this will have both quantitative and qualitative components to build a rounded picture of not only what happened but also how and why it happened. It may draw upon existing empirical and archival data and generate additional evidence through interviews, facilitated group discussions, questionnaires or field visits.

In the case of the Oxfam evaluation, the methodology for assessing the partnership broker approach had two components: (a) desk research involving analysis of the documents provided by Oxfam and the broker; and (b) participatory research involving interviews with the broker and the lead protagonists in the partnerships, using a combination of open and structured questions to draw out both directive and unsolicited feedback.

Table 1.0 below outlines a work plan which can be used to assess the broker approach, focusing on tracking, estimating; assessing, reviewing, reflecting and comparing elements of evaluation activities [2].

Table 1.0 – Methodologies and sources of data for addressing different elements of evaluation

| Element of Evaluation | Purpose | Methodology | Primary Source of Data |

| Tracking activity and output of the brokering approach and the broker | – Develop an understanding of the partnership landscape: design, dynamics, life cycle stage, management, outputs – Collect, collate and interpret recorded data of broker’s commitments, activities and outputs |

Desk research | Documents provided by the partnership and the broker(s) |

| Estimating impacts of activities / projects | Identify outcomes and measure these against partnership programme goals | – Desk research – 1:1 interviews |

– Documents from partnership / broker / partners / partner organisations – Protagonists from partner / project organisations |

| Assessing the brokering approach’s efficiency and effectiveness | – Explore the efficiency of the decision-making and implementation processes – Explore the ‘value added’ to the partners of a partnering approach and the impact of the partnership programme on vulnerable communities |

– Field visits – 1:1 partner interviews |

Protagonists from partner organisations |

| Reviewing the brokering approach’s value for each partner | Draw out the challenges and benefits of the partnership brokering approach | – Field visits – Selected 1:1 partner interviews |

Protagonists from partner organisations |

| Comparing the brokered partnership paradigm | Explore the appropriateness and sustainability of the brokering approach with other non-partnership alternatives for achieving the goals | – Desk research – Peer discussion and review |

– Interview notes – Data and documents from partnership |

Evaluating broker approach as a paradigm

In the field of cross-sector partnerships for sustainable development, we find both brokered and un-brokered partnerships as well as projects delivered through project management or similar structures. Evaluation can be used to assess comparatively the broker approach as a paradigm.

When Oxfam closed its Barbados office, it decided that a more gradual approach to leaving the English-speaking Caribbean region should be taken. It considered the partnership broker approach to be the best strategy because it would support sustainability of the project activities after Oxfam’s exit since the project would be owned by the local partners; and it required fewer manpower and financial resources.

An assessment of the comparison of the broker approach with the project management/ country office approach was part of the scope of the evaluation. This envisaged an examination of the wider impact on the relationships and the interactions between Oxfam and its local stakeholders and partners and the cost effectiveness and efficiency of the broker approach.

Evaluation of cost effectiveness and efficiency requires a comparison of the investment in the broker approach with a country office or some other structure and/or with existing local projects delivered by project managers and project offices. Despite the different attributes and dynamics each approach has, it is helpful to find a stand-alone project with a similar time frame and outputs which are closest to the brokered approach for a like-for-like comparison. The most comparable information is likely to be in the use of resources and assets: staff costs, set up and operational costs (property rental and maintenance, utilities, office equipment, IT equipment, telecommunications, office supplies, legal, banking and other business support services etc). For instance, the expenditure for a project team led by an expatriate project manager and several support/administration staff from a rented office is likely to be higher than the costs for a more mobile, local partnership broker working from home. In absolute cost terms, therefore, it may be more efficient and cost effective to recruit a local broker with local knowledge and experience and able to keep overheads manageable. In the case of Oxfam, this was certainly the case.

However, the benefits from a broker approach go beyond financial considerations. As was evident in the case of the Oxfam scenario, the partnership broker allocated more time to building and supporting the partnership activities than on administrative and back-office activities. This had a critical impact on the quality of the relationships between the diverse stakeholders and on the day-to-day management of the partnership initiatives. The multi -tasking nature of partnership brokering can require management of a wider set of commitments than would be typically involved in a single-focus project. These can be met through outsourcing. For instance, Oxfam had a wide range of activities and requirements which it addressed by using bought-in research and specialist consultancy services whenever these were needed to support its core objectives. These multiple tasks were achieved without the benefit of an office and without additional ‘in-house’ staff.

Evaluating a broker’s performance

The Guidance Note 2 ‘Assessing a Broker’ in The Brokering Guidebook [3] covers the necessity of assessing a broker’s performance and recommends that a partner’s assessment of a broker can be done on a formal basis (for example, through the use of a questionnaire) or on an informal basis (for example, through discussion or interviews with the partners).

The Oxfam evaluation offered me an opportunity to build on the Guidance Note to offer one ‘formal’ evaluation framework –a questionnaire driven performance appraisal tool [4] that seeks to build a rounded picture of a broker’s performance by collecting feedback from a number of sources who would normally work with the broker in a partnership.

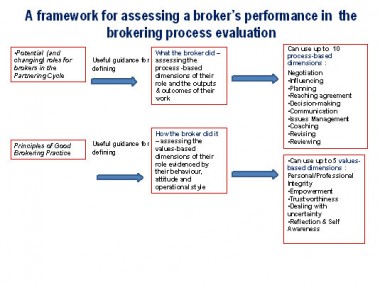

A rounded evaluation can help generate information in three areas of the broker’s performance in and contribution to a brokered partnership:

- What the broker did – this equates to finding evidence of the specific fact-based dimensions of the brokering role, that is, the brokering skills the broker applied and his/her output in terms of the activities he/she delivered. This can be assessed by analysing the monthly and mid-term reports of the broker’s commitments, activities and deliverables, by reviewing any logs or journals the broker might keep as part of their reflective practice, and by drawing from the interview with the partnership broker;

- How the broker did it – in terms of his/her behaviour, approach and style. This equates to ascertaining the values-based dimensions of the brokering role and the broker’s ability to demonstrate his/her adherence to good brokering practice. This can be achieved through an interview with the partnership broker – as a reflective self-assessment of his/her brokering journey – and also from interviews with the partners;

- What impact the broker had – in terms of how his/her skills, output and behaviour combined to influence the pace, direction and outcomes of the partnership programme.

Conducting a partnership broker’s performance assessment in this way offers benefits to both the broker and the partners. The broker gets the opportunity to relate his/her brokering journey in their own words and to get feedback on their approach to partnership brokering, identifying strengths as well as areas where they could develop further. The partners can give feedback in a systematic way on the broker’s approach to both the partnership and to brokering, building a more rounded picture of his/her performance. It also enables the evaluator to do some ‘triangulation’ between the assessments of several people.

The diagram below summarises how criteria combined from the roles a partnership broker plays in the partnership’s activities and the principles which underpin good brokering practice can be used to build an evaluation framework.

The rounded evaluation approach can be used at different points during the life cycle of a partnership: for instance, at the completion of all or each of the four phases in the partnering cycle; when exiting from a partnership or handing over responsibilities to a partner; and when the broker is moving into a newly defined role or handing over to another broker.

The rounded feedback process will yield information which then needs to be analysed, synthesized and presented in a format which the broker and the partners can use. In my experience, it is helpful to have a combination of (a) a spider web diagram, recording the average total ratings from a number of partners and other stakeholders in a high level and simplified shape; and (b) a feedback report, providing a more detailed overview of the results to highlight the broker’s main strengths and areas where he/she might like to develop further. The spider web diagram serves as a useful visual summary of the results of the assessment, showing where the variations and similarities in assessment exist. It can be used in several ways: to support discussions with the line manager around the current reality; to develop a personal and performance development plan for the broker; and as one of the tools in monitoring and reviewing the brokering approach and how it is contributing to the work of the partnership.

More information on the rounded evaluation framework and the appraisal tool is provided in ‘A Tool for Evaluating Brokers : A 360° Approach to Evaluate a Broker’s Impact on Partnerships’ , a copy of which can be obtained from Partnership Brokers Association (PBA) or from the author.

As the work on brokering evaluations continues, it will yield more tools, methods and approaches as well as case studies from a wide range of contexts. Such a body of knowledge will play a crucial role in building evidence, knowledge and understanding of the importance of partnership brokering; and in developing partnership brokering capacity of brokers, brokering units and others committed to high standards in partnership brokering practice and outcomes.

Author

After a career in the corporate sector, Surinder Hundal is now working specifically in the field of cross-sector partnerships, partnership brokering and partnership evaluation. She works as an independent accredited partnership broke and as a specialist in corporate social responsibility. She sits on the Board of the Partnership Brokers Association (PBA), the international professional association for partnership brokers. She holds a post-graduate certificate in Cross-sector Partnerships from the University of Cambridge. Surinder has worked in Asia Pacific, Europe, the USA, the Middle East and Africa, principally in telecommunications businesses such as Nokia and BT, where she led multi-faceted communications, strategy, marketing, corporate responsibility and partnership development roles. She also led policy and communications at International Business Leaders Forum. Surinder can be reached on surinder@rippleseed.com

[1] See partnership typologies developed by Ros Tennyson in The Partnering Toolbook : An Essential Guide to Cross-Sector Partnering, IBLF, 2007

[2] It is adapted from materials developed by The Partnering Initiative and its 4-phase Partnering Cycle framework for partnerships for sustainable development. http://www.thepartneringinitiative.org

[3] The Brokering Guidebook: Navigating Effective Sustainable Development Partnership (2005), Ros Tennyson, International Business Leaders Forum – pages 23- 30

[4]‘A Tool for Evaluating Brokers: A 360° Approach to Evaluate a Broker’s Impact on Partnerships’ developed by Surinder Hundal. It can be obtained from Partnership Brokers Association or from the author on surinder@rippleseed.com