Abstract: This paper explores the interesting phenomenon of units or organisations that have been developed with a specific and recognisable partnership brokering remit – even if that term is not explicitly used. In the early days of the Partnership Brokers Project, 2003, the focus was very much on partnership brokers as individuals. Perhaps, back then, no one envisaged that there was an organisational version of the partnership brokering function even though one of the cited examples below (Krakow Development Forum) had been set up and run successfully as early as 1993. An ‘ah ha’ moment was when working with the Partnership & Cooperation Unit at the African Development Bank over a two year period (2008-9) when it became increasingly clear that the team was performing an ‘internal’ partnership brokering function as a unit.

What follows is an attempt to characterise these types of entity, what role(s) they fulfil and how they operate – examined in more depth by an overview of three comparable but contrasting examples from quite different contexts and established with somewhat different intentions.

It is early days, and this paper is simply a suggestion of an interesting subject worthy of further study rather than a definitive piece. If anyone reading this has other examples of these kinds of entities, the author would be grateful to know about them and perhaps to identify ways of taking this exploration further.

New mechanisms for brokering collaboration: the emergence of partnership brokering units and organisations [1]

A ‘partnership broker’ is defined as:

“…an active ‘go-between’ who supports partners in navigating their partnering journey by helping them to create a map, plan their route, choose their mode of transport and change direction when necessary.”[2]

The Partnership Brokers Association (largely, but not solely, through its training programme) characterises partnership brokering activities and approaches as fluid and subject to considerable change in both emphasis and style at different phases of the Partnering Cycle (see Box 1 below).

Box 1: Typical partnership brokering activities around the partnering cycle [3]

| Phase in the partnering cycle | During this phase partnership brokers are likely to be helping partners to: |

| Scoping & Building |

|

| Managing & Maintaining |

|

| Reviewing & Revising |

|

| Sustaining Outcomes |

|

This range of activities suggests a level of complexity and subtlety – the concept of partnership brokering is, it seems, rapidly becoming more sophisticated. It is no longer understood solely as a new kind of professional role undertaken by individuals (whether internal or external to the partnership), it is increasingly taking the form of a new kind of delivery mechanism requiring different kinds of organisational structure either within existing organisations or as independent, specially created entities. (See Box 2)

Box 2: Partnership brokering undertaken by individuals or organisations [4]

| Individuals | Organisations / Units | |

| Internal | Employee operating as a partnership broker from within one of the partner organisations | Specialist unit within an organisation supporting a range of partnerships |

| External | Independent specialist offering a portfolio of partnership brokering services | Independent organisation operating as a catalyst / intermediary between partners |

Partnership Units

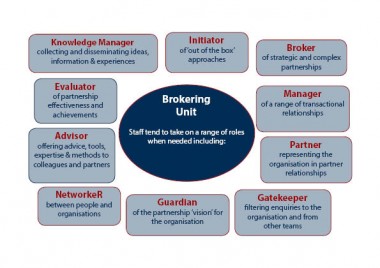

Specialist partnership teams are increasingly being established in larger organisations including multinational corporations, government departments, international NGOs as well as within some bilateral and international agencies. These units are expected to bring multi-sector experience and partnering expertise into their organisation. They typically develop internal partnering guidelines and support systems for a range of partnership activities. They also provide a ‘one-stop shop’ for external organisations seeking to become partners as well as creating a gate-keeping function to ensure that the organisation’s partnering activities are well coordinated and operating within appropriate boundaries.

In some organisations – presumably in recognition of the diversity of their activities (see Box 3 below) – these units are positioned and described as having a ‘brokering’ function. Some are even described as Partnership Brokering Units.

Box 3: Typical activities of a unit undertaking partnership brokering activities within an organisation [5]

Working in such a unit is not necessarily any easier than operating as a single individual – many of the same challenges apply. It is a common cry that the work of the unit is ‘not understood’ and that the skills of collaboration process management (aka partnership brokering) are so subtle as to be virtually invisible when measured against more conventional forms of intervention. It can be a struggle to justify the allocation of funds for what is seen as a nebulous function. It is also not uncommon for such units to be used as a dumping ground for the elements of partnering that others find tedious (e.g. contract management) and / or as places to relocate staff who may not have the necessary competencies, experience or insight to undertake the brokering function with confidence.

But these are early days – decision-makers in organisations need to understand more precisely what is required to support their partnership aspirations and those in brokering units may have to become more assertive in presenting what it is they do and explaining why it could make a significant difference.

Partnership / partnership-type organisations: [6]

So how does this compare to the growing number of independent (or quasi-independent) partnership brokering organisations – whether small, new entities created for this purpose or well established, possibly large international organisations seeking to re-define their role?[7]

Independent intermediary organisations can be found in many different contexts operating as ‘for-profit’ consultancies or as ‘not-for-profit’ social businesses or NGOs. Such organisations function as:

- Teams of specialist staff

- Networks of more independent consultants or

- Complex organisations with different divisions undertaking different brokering functions.

Whatever the type of organisation, those involved (many now formally qualified partnership brokers who have graduated from the Partnership Brokering Accreditation Scheme) deploy a range of intermediating skills and offer a portfolio of partnering and / or partnership brokering services (see Boxes 4 and 5). Such organisations can work at either operational or strategic levels.

Box 4: Typical activities of an independent organisation undertaking partnership brokering functions [8]

Despite the global emphasis on partnerships as an important mechanism for achieving sustainable development, even the most competent and experienced brokering organisations struggle to get people to understand what they offer and why their services matter.

Box 5: Extract from the logbook [9] of a partnership broker working in an independent brokering organisation (2011)

|

Familiarity with partnership brokering concepts has fundamentally altered my perception of what it is that we should be doing as a small, specialist consultancy. I increasingly see the possibilities of partnership approaches in many of our projects, to the point that I now integrate the concept in virtually all project proposals. One of the most important outcomes of this realization is that a focus on partnerships and on partnership brokering will fundamentally change our approach to the way we work. Three service concepts taken from recent experience with clients highlight how partnership brokering will become more of a core service offering:

However, it is clear from this that we are more often than not advocating and scoping partnerships, rather than building, implementing and evaluating them. In other words, our current activities tend to be in the early stages of the partnering cycle. This is in part a function of the immaturity of the market for partnership brokering and in part due to our newness to the market (less than four years). |

Example 1: KRAKOW DEVELOPMENT FORUM (KDF)[10]

The KDF operated between 1993-1996 as a partnership of individuals representing organisations from business, government, universities and civil society. Their common motivation was to mobilise partnership action between their organisations for the benefit of the City of Krakow. The aspiration was to contribute to the economic, social and environmental improvement of Krakow as Poland embarked on market and democratic reform following the collapse of communism in 1989.

Origins / Drivers:

The KDF was created in 1993 as Krakow and Poland re-organised following the re-establishment of an elected local government in 1991. The KDF was established by a group of 21 individuals from all sectors, including the Mayor of Krakow who participated in a workshop with international business leaders organised on the occasion of a visit to Krakow by the Prince of Wales. By 1996, 88 individuals were involved, representing 40 organisations. The driver was to find ways of defining the roles and responsibilities for business, government, academia and civil society at the city level as Poland transitioned from a centrally-planned to a market economy and from communism to democracy.

Operational characteristics:

The KDF was designed to enable and promote collaborative work, not to engage in project implementation itself. This was a partnership set up to identify opportunities, problems and to organise responses based on the resources and competencies of its members in the first instance. The KDF registered as an Association of individuals with institutions as supporting members. Individual and organisational members paid membership fees to maintain a small secretariat, which brokered partnerships around ideas and opportunities, organising regular meetings and interactions involving local organizations and international investors interested in Krakow. From the very beginning, it was intended that the KDF should be a temporary or transitional organisation with the idea that it would be disbanded once the sectors had become more defined and consolidated in their roles and responsibilities for the development of Krakow, especially with regard to attracting international investment to the city.

Aims & achievements:

The aim was to identify and engage leaders from emerging civil society, business and government sectors in joint action for the benefit of Krakow by identifying, organising and resourcing interesting initiatives, projects and programmes. Priorities were projects, which could not be dealt with by any single sector acting alone, such as the revitalisation of Krakow’s historic Jewish district (Kazimierz) and the industrial area of Krakow around the former Lenin Steelworks (Nowa Huta). The main achievement and legacy of the KDF was that it created and inspired collaborations around priority City development projects, which continue to this day. Thanks to the KDF network, individual and organisational collaborations developed, flourished and took on a life and dynamic of their own. In short, the KDF helped establish a partnership culture in Krakow, which provided impetus for economic, social and democratic reform. Many KDF members went on to play major roles in Poland’s reforms, its access into the EU and economic growth.

Challenges:

Once it was agreed that the organisation had fulfilled its purpose, the KDF was disbanded in 1996 by its members. The main challenge for a transition or temporary organisation like the KDF is that of documenting its impact and significance as it was by its very nature “invisible” in its partnership-brokering role (although, at the time, this term was not used). For partnership brokers, the key thing is to recognise that a temporary or transition-brokering organisation can be truly transformational in many situations, where roles and responsibilities of existing organisations are ill-defined and / or are perceived to have fallen short.

Current status and / or future aspirations:

Although the KDF does not exist as an organisation, its legacy of partnership action lives on. Some of those who were involved in its design, operation and dissolution have subsequently identified other situations in which temporary partnerships are appropriate and a real option for accelerating development. The KDF experience suggests that post-conflict situations where social and political institutions must be defined anew are the most appropriate for this kind of temporary partnership brokering entity to help evolve collaborative solutions.

Example 2: Start Network (formerly the Consortium of British Humanitarian Agencies) [11]

The Start Team sits at the heart of a consortium of nineteen humanitarian civil society organisations (Start Network). These organisations have a collective commitment to ‘accelerating crisis response’ as a contribution to fostering more resilient communities. The Consortium was officially formed in 2010 at which point a small team was hired to function as the ‘programme management unit’. Over the course of the pilot (first two years) this name was an accurate descriptor for the team in the middle as it was mainly responsible for the coordination and management of the grant. However, as the funding ended the role of the team changed considerably. The two members of staff (Director & Advisor) that were retained focussed on exploration, innovation and the development of new partnerships. On behalf of the consortium they met with a wide variety of organisations and advisors exploring new opportunities for the consortium. Now, after four years, the consortium stands to receive considerable amounts of funding which changes the nature of the central team again. The Start Team will grow in size (five members of staff) and focus on facilitation, coordination, management and innovation, hopefully combining the traditional Secretariat functions with less traditional functions that focus on pushing the boundaries of the consortium and investing in transformative opportunities.

Origins / drivers:

The main driver is that the humanitarian civil society sector is under pressure to remain relevant. Donor dependency, bureaucracy and inertia have caused the sector to be inward looking and incapable of building new partnerships and operational modalities to address the increasing caseload of humanitarian disasters. This driver is also closely related to the awareness in the Start Team that the business model of humanitarian NGOs is dysfunctional, as NGOs are limited to respond in crises that gain media and / or political interest. The ability to access larger pools of funding (comparable to the UN and Red Cross / Red Crescent) is also a strong driver for the members of the consortium.

Operational characteristics:

The Start Team consist of a Director and 4 others. The organisational structure is in practice flat and everyone’s views and opinions are valued. The Start Team often gathers in informal spaces (such as coffee shops) for conversations about the Network, to try and ‘make sense’ of the various priorities and opportunities. In the future the Start Team aims to be better embedded in the membership and in the near future the team will be strengthened by five secondments which will be based in member agencies 4 days a week and come together with the rest of the Start Team one day a week. The team regularly writes ‘options and discussions papers’ for the Consortium Board, but the uptake and influence of those papers have varying degrees of success. The Team continues to struggle with ways of including and engaging the member agencies as much as possible, and it is hoping that the secondment model will work. The Team is focussing intensely on partnership brokering to make its work more effective. In terms of governance, the Start Team reports to the Consortium Board, as well as a Chair and Vice-Chair and interacts regularly with an Advisory Group. In addition to the formal governance structures the team seeks regular advice and assistance in shaping its work from independent and external contacts or specialists.

Aims & achievements:

One of the biggest achievements until now is that the consortium has stayed together during the course of a difficult and uncertain period. This is due to both the members’ commitment and to the team’s persistence and hard work. Furthermore, the team has played a large role in getting the Consortium to the point where it is entrusted with large grants from the UK government. Less tangibly, but importantly, the Start Team has kept collaboration strongly on the agenda, and perhaps opened agencies’ eyes as to what can be achieved in collaboration. Lastly, the team has arguably developed some exciting ideas for the Consortium and represented the Consortium robustly to other actors who have shown a strong interest in the Consortium’s aims.

Challenges:

Systematic engagement and interest from the consortium members is seen as the biggest challenge for the team. In fact, the Consortium sometimes seems more attractive to outsiders than those inside. Sometimes the team feels that Consortium members do not understand the nature of their work or why the team can feel overwhelmed by micro management and endless processes. The board can feel left behind when things change fast and sometimes express concern that the team is less consultative than it should be. Another practical challenge is how to keep the transaction costs (often time rather than money per se) of collaboration between so many different agencies as low as possible. A last and recent challenge for the team is to persuade the board that the Consortium should be: a) open to non UK agencies and new members b) accepting independent representatives on the new and smaller Executive Board and c) appointing an independent chair.

Current status and / or future aspirations:

The current status is that the Start Team is growing while it is also trying to establish ‘decentralised capacity’ within the membership. The latter is a future aspiration to keep ownership with the member agencies and keep engagement high. Another aspiration is to manage the financial aspects and the related politics and risks that come with it in an effective manner. It is the future aspiration of the Start Team that the Start Network spins of as an independent entity so that it can be seen as a true neutral brokering unit.

Example 3: India Backbone Implementation Network (IbIn)

Description:

IbIn was initiated by the Government of India Planning Commission in 2012 and was formally launched in April 2013. The movement has been modelled on the ‘Total Quality Movement’ (TQM) of Japan, which the manufacturing sector recognised as an international benchmark for excellence.

The primary aim of IbIn can be best described as follows:

Origins / drivers:

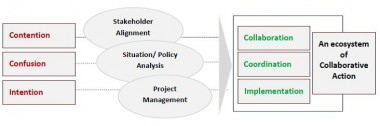

While preparing its 12th Five Year Plan, the Planning Commission undertook an analysis of what would be required to successfully implement the Plan. The analysis revealed that the root cause of the poor implementation of plans and projects in India is contention amongst stakeholders, and poor coordination amongst agencies. Such bottlenecks are at many levels in the system: at the Centre; in the States, and in districts and cities too. Efforts to relieve these bottlenecks from top down, after they arise, have now become necessary. However this approach is not sustainable, because bottlenecks will keep arising within the system unless root causes for the bottlenecks are addressed. Taking cognizance of this, the Planning Commission in the 12th Five Year Plan identified the need “to establish an effective ‘backbone’ capability which will provide strength to multi-stakeholder policy and implementation processes”. Thus IbIn was born.

Operational characteristics:

IbIn’s capabilities include stakeholder alignment, project management, and policy development processes, all of which require skills (for facilitation of collaboration / coordination) as well as domain knowledge (pertaining to the specific subject matter or sector). Generally no single entity can provide both the process management skills and the domain knowledge. Therefore, IbIn is designed as a network that will bring together combined capabilities of partner organisations [12] as required. The first node of IbIn, for example, is housed in the India@75 [13] Foundation that aims to promote voluntary initiatives by citizens and corporations for the development of India.

Several agencies and organisations have developed techniques and tools in the areas of stakeholder alignment, policy analysis and project management. IbIn calls these process experts, IbIn Enablers, whose services are made available to IbIn Channels for sharing, co-creating, coaching and consulting in these areas. IbIn Sponsors are supporters of the IbIn movement, providing financial assistance to nodes and specific IbIn projects and initiatives, as well as contributing human resources and other forms of support.

IbIn has set up IbIn Nodes: lean cells, typically located within larger institutions, committed to promoting and catalysing the IbIn movement. The IbIn Nodes diagnose the issue at hand, and then match the specific needs of a project to the capabilities of the IbIn Enablers in the ‘backbone network’, thus playing the role of market-makers. They also act as knowledge repositories and aggregators of toolkits and best practices. In this way, the IbIn movement promotes widespread capabilities in the country to systematically convert confusion to coordination, contention to collaboration, and intentions to implementation.

Current status:

In the ten months since its launch, IbIn’s focus has been on improving business regulations in Indian states; promoting the growth of micros, small and medium size enterprises (MSME) clusters; improving industrial relations; enabling access to affordable medicines; building capacity for better government service delivery; improving grassroots governance; increasing rural livelihoods and improve care for the elderly amongst other initiatives. IbIn is also working on development of techniques and tools for collaboration and coordination for dissemination across the country.

Challenges:

The progress made by the IbIn movement, which was launched without any seed funding, has been entirely due to the enthusiasm and the commitment of partners who believe that an IbIn-like process is essential for India’s progress. To further strengthen this movement, which has the potential to make a significant contribution to accelerate India’s development, more partners are required with more support from each of them.

The core team is led by Arun Maira (a member of the Planning Commission) with a number of young and enthusiastic professionals seconded (typically for a year) from a range of companies. The intention is to keep core costs to a minimum and the bureaucracy light. However, there is a question for some as to whether this is realistic if the hope is to reach scale and impact in the near-term. Critics say the change IbIn seeks will take a long time, and so it may. The core team believe that if such a movement had started 10 years ago, India would be in a much better place than it is now – but they recognise that there has to be a start and this is a time to lead and to act.

Observations and initial conclusions

The three examples cited above reveal some interesting things in that they:

- Have all been developed in response to perceived inadequacies in existing systems

- Are all examples of a ‘voluntary’ association of agencies

- Are all somewhat open-ended and non-hierarchical in their structure and management

- Build on the notion of the entity having, essentially, an inter-mediating / brokering function

- Explicitly promote collaboration / partnership as an appropriate mechanism for achieving quite ambitious sustainable development goals

- Seek to distribute activity and initiative rather than centralise and / or control it

- See impact rather than growth of the entity as the measure of success

They also raise some questions that give pause for thought with regard to:

- Such entities being potentially under-valued because the way they work is supportive rather directional (less true of Start Network)

- The challenges of operating with little or no core funding (again, this is less true of Start Network)

- Building an institutional presence (that can hold its own with other institutions) without becoming institutionalised

- Their focus on collaboration as a sustainable and inclusive process in a world where projects are usually what counts

There may be a series of issues specific to this emerging model that could usefully be explored including:

- What combination of skill sets may be required for those operating in partnership brokering units or entities?

- How are such forms of partnership brokering entities best characterised in the public domain?

- What the implications are of ‘success’ equaling ‘redundancy’ (as in the case of the Krakow Development Forum and may be the aspiration of the other two cases)?

- What constitutes ‘success’ for an entity of this type? And how will the entity know when it has achieved its goals?

The growth of partnership brokering units and organisations seems to be significant. Is it worthy of more deliberate research and analysis to understand better what works and what doesn’t? It is relatively early days, and it remains to be seen whether such entities can have real impact in the promotion of more effective partnerships for sustainable and inclusive development – but it seems to be a phenomenon worth monitoring.

Author

Ros Tennyson has over 20 years experience in cross-sector partnering and partnership brokering. From 2001-2007 she was co-Founder and co-Director of a Post-Graduate Certificate in Cross-Sector Partnerships at the University of Cambridge Programme for Industry. From 2003 to 2009 she was founding Director of The Partnering Initiative (IBLF). In 2003 she co-founded the Partnership Brokers Accreditation Scheme and in 2011 the Partnership Brokers Association. She has written a number of pioneering case studies, think pieces and tool books on aspects of partnering including: The Brokering Guidebook: Navigating effective Sustainable Development Partnerships. She has worked in all main sectors in the UK and overseas and has undertaken a range of training and partnership brokering work in the Humanitarian and Development sectors including: AusAID, CBHA, CDAC Network, DFID / BRAC (Bangladesh), GIZ / Nabard Bank (India), UNDP (Cambodia) and World Vision International.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the following people for their invaluable in-puts into the three examples: Rafal Serafin – Krakow Development Forum; Marieke Hounjet – Start Network; IbIn team – India Backbone Implementation Network.

[1] This builds on an earlier paper compiled by Surinder Hundal and Ros Tennyson after working to build the partnership brokering capacity of the Partnership & Cooperation Unit (ORRU) of the Africa Development Bank in 2009 and 2010. ORRU is responsible for mobilizing trust funds, co-financing, technical cooperation and strategic partnerships arrangements with development partners to enhance the operations of the Bank in Regional Member Countries. The Unit serves as a central focal point for the Bank’s partnerships management and monitors the implementation progress and results of the Bank’s partnerships and cooperation work.

[2] This definition was first used in The Brokering Guidebook available from: www.ThePartneringInitiative.org

[3] Copyright: Partnership Brokers Association. For more general information on The Partnering Cycle see The Partnering Toolbook available from www.ThePartneringInitiative.org

[4] First cited in the Brokering Guidebook

[5] Copyright: Hundal & Tennyson

[6] A ‘partnership type’ organisation refers to an entity operating as a consortium, coalition or active network exhibiting many characteristics of a partnership without actually using that term.

[7] For example, certain UN agencies, some bi-lateral organizations and a few international NGOs have begun to explore how they can re-position themselves as ‘catalysts’ or ‘intermediaries’.

[8] Copyright: Hundal & Tennyson

[9] The log book was part of their work to become accredited under the Partnership Brokers Accreditation Scheme

[10] A brief overview of how KDF started is available from PBA on request – info@partnershipbrokers.org

[11] A detailed case study charting the story of the first three years of this consortium is available on the Start Network website (http://www.start-network.org/) or the PBA website

[12] The Partnership Brokers Association is one such partner

[13] See website http://www.indiaat75.in