Abstract: This article provides an overview of a review designed to evaluate and strengthen partnerships within a cluster of heritage organizations[1] in Newfoundland, Canada. This project took place at a time when a strong and sustainable partnership was becoming critical to the future survival of the cluster. It highlights the tools and techniques used by two external brokers[2] invited to review the cluster and its members to understand the current status and effectiveness of its internal partnerships[3]. The results of the review were used to guide and build the organization towards a new partnership model utilizing a combination of partnership brokering and community development best practices. The authors describe this process and the application of the review findings; and also highlight the intersection of these best practices and key lessons along the way.

Reviewing as a Mechanism for Building Sustainable Partnerships: A Heritage Partnership in Newfoundland and Labrador

Introduction

The Northern Peninsula Heritage Cluster is a network of local heritage organizations located on Newfoundland’s Great Northern Peninsula. In 2010, these groups began working together to provide a co-ordinated approach to the delivery of visitor heritage experiences and interpretation in the region. In April 2012 and after hearing about the Partnership Brokering model and approach[4], the Heritage Cluster Co-ordinator and Advisory Group invited the authors of this paper, to assist with strengthening the partnership and sustainability of the organization, as it prepared to move into a new phase in its development. Using a combination of brokering techniques, review tools and community development approaches the authors worked with the group to carry out an assessment of the existing partnership. Based on the findings they designed and delivered (with partner support) a series of workshops and planning sessions to help strengthen and build the partnership and the Heritage Cluster network as a whole. This paper provides an overview of the review and community development techniques that were used, as well as key lessons learned from our approach.

Background and context

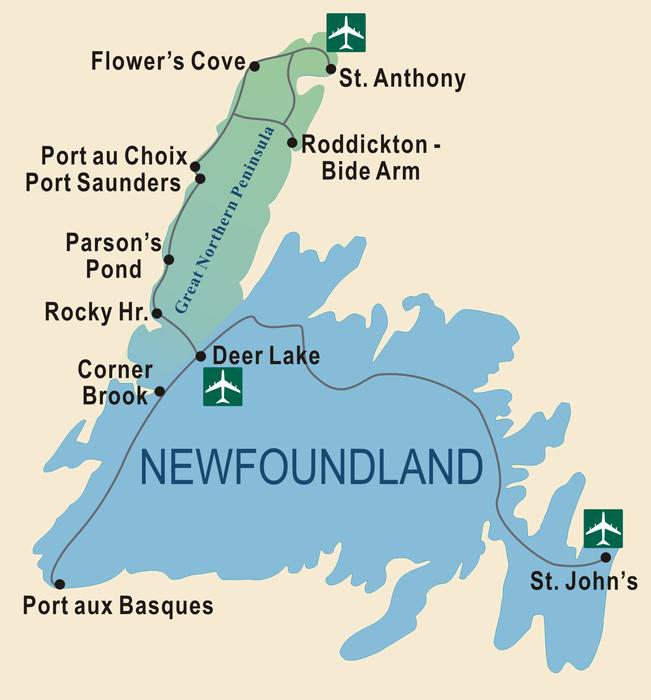

The Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland and Labrador has a vast geography, encompassing approximately 17,500 kilometres2. There are approximately 17,000 people living in 69 communities along the coast. These communities were built on the fishery and forestry sectors but have since diversified and have begun to showcase their history, culture and geography through a developing tourism industry. Through numerous initiatives, many heritage sites have started to develop museums and interpretive products that highlight the history of the fishery, medical influences on the peninsula, unique flora and fauna, and other features. (Map credit: www.northernpeninsula.ca)

Due to the sporadic location of the heritage sites throughout the peninsula as well as the number of visitors they are attracting, the need for a Heritage Cluster emerged. This initiative was developed through a partnership between the Red Ochre Regional Board and Nordic Economic Development Corporation, with both groups supporting the heritage sites in the region. The Department of Tourism, Culture and Recreation, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, supported the initiative via the provision of funding to assist in creating the Cluster. In addition, other government departments have also been active partners. This Cluster has and continues to endeavor to give strength in numbers to these groups, create more promotion potential and to provide the members with the opportunity to learn from each other.

Review Tools and Techniques

When designing our partnership review, we utilized a variety of different tools and techniques to give the authors and the group as broad an understanding as possible of the current state of the partnership. The components of the assessment included:

- Advisory Group Meeting – we met with this group to gather a history of the Cluster and its work to date, along with information on key players, processes and structures in place

- Individual interviews – we organized a series of interviews; one with each organizational member of the heritage network. Wherever possible we tried to arrange a meeting with several members of the local heritage organization, but sometimes (due to lower volunteer numbers) it was only possible to connect with the lead contact for the group.

We felt these individual interviews were important to get a realistic view of the current state of the partnership and we used the questions to ascertain if members were seeing benefits and felt engaged, and to understand their objectives and priority focus areas. When we designed the questions, we referenced many of the tools in the Partnership Brokering Toolbook[5], such as the coherence assessment questionnaire and partner assessment tool. The interviews asked the following questions:

|

- The Wilder Collaboration Factors Inventory– This inventory (http://surveys.wilder.org/public_cfi/index.php) explores the factors necessary for successful partnerships. During this process we selected a number of the factors (including history of collaboration, respect and trust, compromise, communication, vision and others) and asked the group to assess the Heritage Cluster with regards to particular factors. The assessment was carried out using audience response technology, which allows participants to provide answers and vote on their priorities using hand-held keypads, with the results viewed by the cluster as a whole. This process identified a few key areas where the group was working well and also a few areas where the partnership could be improved. This focused our agenda for the next steps of the partnership building process.We summarised the interview results into a presentation (ensuring individual site comments remained anonymous) and delivered this to the advisory committee, before presenting it to cluster members at the first workshop.

Engagement Tools and Technologies – wherever possible we tried to use tools which made the sessions, reviews and discussions as engaging as possible. These included:

- Polling– During the process of identifying areas to improve upon and actions and next steps, Turning Point, an audience response system from Turning Technology was used. This technology allowed individuals to contribute their opinions anonymously. For instance, when deciding on items for their constitution (executive structure, decision making policies) voter response keypads were used.

- Deliberative Dialogue Techniques – As a part of this process we endeavored as much as possible to have deliberative dialogue opportunities so that the partnership could evolve through idea exchange and debate. Through this process, an issue or idea of importance to the group was selected for discussion in small groups. The groups were facilitated so that everyone had a chance to speak and so that conversations would stay on topic. The ideas from the groups were collected, themed and put into slides to report back to the group. From those slides, voter response keypads were again used to prioritize the ideas to move forward on.

Partnership Building

As we began the partnership building process, we had several goals in mind, many of which also aligned with community development objectives. These included:

1. Group sustainability including resource sustainability as well as building the ability and interest of partners to manage and take forward the actions and projects of the network.

2. Building empowerment and capacity among group members to lead and deliver projects for the network

3. Creating ownership and commitment by group members. Our goal was to see tangible commitments by members to supporting and taking forward the work of the partnership. We also hoped that this contribution would become an expectation of all partners in the network.

In order to work towards these objectives, we held a series of workshops with the group (at several of their regular group meetings). Each workshop took between half a day and a full day to deliver as they focused both on a combination of partnership-building and ensuring the correct structures and processes were in place to sustain the group as an entity over the long-term.

Initially the planning of the workshops took place with resource people and the Cluster Advisory Group and (once the Heritage Cluster had identified its new structure and executive) with both resource people and the chair of the Cluster. This aimed to address the critique (heard in the interviews) that there was no or little involvement from heritage group members on the advisory group for the project. This had meant that members were not involved in planning out the direction of the network and there was a sense that this was leading to a lack of ownership of the Cluster. This ownership was critical where the group needed to move to a more self-sustaining structure. The workshop planning also utilized the skills of a wide variety of support organizations, i.e. the authors had skills in partnership building whereas staff in other organizations had experience in group governance, structure and processes.

Delivering the Workshops

The first workshop began by presenting the results of the interviews and asking the group to vote on the Wilder Review Questions, using the voter response keypads. The results of this polling were reviewed that evening by the authors and given back to the group the following morning.

After this, and as the workshop continued, we started to address some of the issues raised by the review and moved into the partnership-building phase.

In terms of workshop structure, for day two of the first workshop, participants were asked to discuss the following questions:

|

The second workshop focused on developing a vision and finalizing goals for the Cluster, along with moving forward on action planning items.During the collaboration discussion, a presentation was made on the Partnership Brokering approach and group members were asked what they thought about this and whether the Cluster should be run as a partnership model. Some formal collaboration structures were also discussed as the group was interested in exploring these further.

The final workshop focused on confirming group structure, membership, processes and resource mapping. We used this workshop to get agreement on many of the items that would be incorporated into a group MOU or Partnership Agreement.

Lessons Learned

As part of the project, we feel that there are some key areas which are important to highlight or where we had significant learnings. These include: building ownership of the Heritage Cluster by its members, action planning, resource mapping and the review process.

Building Ownership – We asked a representative of the group to take a lead on a section of the workshop (i.e. for the first workshop, this was around the vision) and as the workshops progressed, we worked to increase the role of group representatives in the meetings. We also asked the Cluster co-ordinator to take a step back in order to begin reducing the group’s reliance upon them.

We asked resource people not to vote on any of the group decision making, but to leave this as the responsibility of the Cluster members.

We also worked to highlight the positive items that came forward from the review – for example, in the interviews we asked participants to identify skills and expertise that their individual heritage groups possessed, which could be shared with the wider network. We were impressed and excited by the diversity of experience and practical skills that they identified.

Action Planning – Throughout each of the workshops we allocated time to action-planning for the network. Four key themes were identified and we asked people to work in small groups based on their interest in a particular theme and to identify actions, tasks and timelines related to these. This worked well for several themes but, for others, there was not the level of interest from group members or the projects identified were large and required significant time and resource commitments. A learning from this process, is to focus initially on a small number of easily achievable projects and small wins, until greater ownership of the network has been achieved. These smaller wins help to build momentum and a sense of group achievement, which can lead to greater willingness and drive to take on larger projects. The delivery of cluster wide action items by group members was a move away from the previous approach, where the network co-ordinator (a paid position) had been working to deliver projects for the group.

Resource Mapping – We used this technique to build on the positive finding in the review of the variety of skills and expertise which group members were willing to share. We initially identified all the resources which were needed for the network to move forward as a sustainable organization and then asked the partners to highlight what they could contribute. Every single resource needed was found within the group, many from multiple partners. This helped significantly to empower and build confidence of the group members. One of the challenges we anticipate is keeping these shared resources in group member’s minds as an option, as it is tempting to go back towards previous models where government funding provided many of the resources.

Review Process – We found that it is important to share widely the review findings with the group and their support organizations, even though some of these findings may be difficult to hear. Where the results may be critical of particular partners, then we found it helpful to present the results in advance to them.

Role of the Broker – Both authors acted in an external broker role with this review. Although known to many members of the Cluster through our work supporting community and regional development, we had not previously been a part of the Heritage Cluster project. We had both been trained as partnership brokers and were able to use many of the tools and techniques provided in the Partnership Broker Association training and resource materials. Based on our experience of this review process we found that it was much easier to do the review as an external, rather than internal broker. If we had been internal brokers, then we feel it could have been very challenging to get the ‘full story’ from partners, particularly during the individual interview stage. As external brokers with no previous attachment to the project, we feel that Cluster members were honest and open with us, in providing their comments and critiques.

Conclusion

While undertaking this initiative, we used a combination of brokering techniques, review tools and community development approaches. Through this process and with the support of the many partner organizations, we have seen the partnership grow and move forward with positive signs of increased ownership, commitment and sustainability.

This paper has provided an overview of the review, partnership building and lessons learned and is a summary of how we developed and implemented this multi-faceted process. We hope we provided a detailed experience and rationale for using a number of approaches and tools to build strong and sustainable partnerships. This building process is a crucial next step for implementing changes identified through a partnership review.

The authors believe that enhancing ownership, commitment, empowerment and capacity of members is key to success in the partnership and that individual organizations need to become active members of the partnership, if the project and the Northern Peninsula Heritage Cluster are to become sustainable over the long term.

Authors

Marion McCahon is a rural community development practitioner and has spent the last 15 years work with rural communities in Scotland and Newfoundland, Canada. Originally from N. Ireland, she now calls Corner Brook in Newfoundland her home. She holds a BTech. (Hons) in Rural Resource Management from the University of Edinburgh and is currently completing an MSc in Managing Sustainable Rural Development. She has been fortunate to work with many inspiring rural communities and community leaders and having worked for many years with National Parks in Scotland, has a special appreciation for community development within Protected Areas. She now works for the Office of Public Engagement with the Government of Newfoundland Labrador and enjoys a diverse role including community based research, partnership development and citizen engagement. She was certified as a Partnership Broker in 2011 and plays an active role in partnership building and development within her region.

Marion McCahon is a rural community development practitioner and has spent the last 15 years work with rural communities in Scotland and Newfoundland, Canada. Originally from N. Ireland, she now calls Corner Brook in Newfoundland her home. She holds a BTech. (Hons) in Rural Resource Management from the University of Edinburgh and is currently completing an MSc in Managing Sustainable Rural Development. She has been fortunate to work with many inspiring rural communities and community leaders and having worked for many years with National Parks in Scotland, has a special appreciation for community development within Protected Areas. She now works for the Office of Public Engagement with the Government of Newfoundland Labrador and enjoys a diverse role including community based research, partnership development and citizen engagement. She was certified as a Partnership Broker in 2011 and plays an active role in partnership building and development within her region.

Nina Mitchelmore has spent the last 13 years doing community development work on the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. With the exception of completing post-secondary education in St. John’s, NL, Nina has lived her entire life on the Northern Peninsula. She currently resides in Green Island Cove, a small rural community on the west coast. She lives there with her husband and two children. Nina holds a BA (Hons.) from Memorial University of Newfoundland. Nina started her career in the public sector in 2007 and now currently works for the Office of Public Engagement, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Through her position with the Provincial Government, Nina is able to continue to work both on a regional and provincial level.

Nina Mitchelmore has spent the last 13 years doing community development work on the Northern Peninsula of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. With the exception of completing post-secondary education in St. John’s, NL, Nina has lived her entire life on the Northern Peninsula. She currently resides in Green Island Cove, a small rural community on the west coast. She lives there with her husband and two children. Nina holds a BA (Hons.) from Memorial University of Newfoundland. Nina started her career in the public sector in 2007 and now currently works for the Office of Public Engagement, Government of Newfoundland and Labrador. Through her position with the Provincial Government, Nina is able to continue to work both on a regional and provincial level.

[1] A heritage organization in this context is a community heritage group whose members work to develop and promote a local natural or cultural heritage site. Examples of sites include: cottage hospitals, fishing premises, museums, natural heritage interpretation centres. and archaeological sites

[2] An external broker is typically an independent consultant or external organisation appointed by the partnership to implement decisions on its behalf. He/she may have also seeded the idea or may even have initiated the partnership.

[3] An internal partnership in this context is a collaboration between sites who are members of the Cluster with the aim of moving forward goals and objectives of the Cluster.

[4] The Partnership Brokering model and approach is presented in the Level 1 Partnership Brokers Training Course run by the Partnership Brokers Association www.partnershipbrokers.org

[5] The Partnering Toolbook; An Essential Guide to Cross-sector Partnering (2003), Ros Tennyson, International Business Leaders Forum