Abstract: In 2012, the Millennium Water Alliance (MWA) commissioned Improve International to conduct an independent evaluation of MWA’s programme effectiveness and provide quantifiable evidence and examples of the value-added (if any) of working in coalition to implement water, sanitation and hygiene programmes in the developing world. The Collective Impact Report (Improve International, 2012) found one of the key added values of working in coalition was the clear improvement in all areas when the MWA began to be professionally managed by a partnership brokering unit. Another key added value is the opportunity for inter-organisational learning and knowledge transfer. This article summarises the findings of the report and highlights the role that the partnership brokering unit played. Plans for addressing the recommendations as part of MWA’s new 3-year strategic planning are also described.

Partnership brokering is helping a water, sanitation and hygiene partnership work towards collective impact

According to the Brokering Guidebook (Tennyson, 2005), a partnership broker operates as an active intermediary between different organisations and sectors (public, private and civil society) that aim to collaborate as partners in a sustainable development initiative. Increasingly, the brokering role is not just undertaken by individuals but also by specialist partnership units and intermediary organisations developing new kinds of delivery mechanisms. The Secretariat of the Millennium Water Alliance (MWA) serves just such a role.

In 2012, the Millennium Water Alliance (MWA) commissioned Improve International to conduct an independent evaluation of MWA’s program effectiveness and provide quantifiable evidence and examples of the value-added (if any) of working in coalition to implement water, sanitation and hygiene programs in the developing world. We decided to use the Collective Impact conditions as a framework to evaluate the partnership. In “Collective Impact,” Kania and Kramer argue that large-scale social change comes from better cross-sector coordination rather than from the isolated intervention of individual organisations. A Collective Impact initiative is a long-term commitment by a group of important actors from different sectors to a common agenda for solving a specific social problem (Kania & Kramer, 2011). Successful collective impact initiatives typically have five conditions that lead to powerful results: a common agenda, shared measurement systems, mutually reinforcing activities, continuous communication, and backbone support organisations (Kania & Kramer, 2011). Susan Davis (co-author of this paper), Executive Director of Improve International, is an accredited Partnership Broker, and recognised the language of partnership brokering in the description of the backbone support organisation:

[It] requires a dedicated staff separate from the participating organisations who can plan, manage, and support the initiative through ongoing facilitation, technology and communications support, data collection and reporting, and handling the myriad logistical and administrative details needed for the initiative to function smoothly. (Kania & Kramer, 2011)

These are among the wide range of roles a partnership broker or brokering unit may perform, reflecting the changes in management priorities and key activities for the partners as their partnership progresses.

The MWA is a permanent coalition of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) working in the water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) sector. It was founded by a core group of its current members to provide an opportunity for donors and NGOs to increase the scale of their operations – with increased impact at lower cost. At first, with limited financial resources, the coalition was managed by its board (made up of representatives of each member). Activities in the first few years were advocacy to the US Government to fund WASH interventions, fundraising for joint programs, and implementation of those programs.

In 2008, MWA was able to hire an Executive Director, Rafael Callejas, who has since been joined by a Director of Advocacy & Communications, Director of Programme Development (Susan Dundon, co-author of this paper), Senior Accountant, Programme Officer, and Programme Assistant. This Secretariat functions as a partnership brokering unit: coordinating the sharing of responsibilities and resources among partners, including project management, relationships with host governments and other stakeholders, and consolidating advocacy efforts for future water and sanitation investments. The Secretariat now also facilitates the dissemination of lessons learned and adoption of best practices, and harmonises specific regional efforts of the world’s leading WASH organisations, in ways that no single partner could. Currently, MWA has 13 members working to assist poor communities in the developing world gain access to WASH.[1]

After almost 10 years of MWA’s existence, the Secretariat recognised that it was a critical time to evaluate the value-added (or not) of working in partnership (the Reviewing stage of the Partnering Cycle (Tennyson, 2005)). While a number of internal and external programme evaluations had been completed in the past, an overall evaluation of the collective impact of working in partnership under the MWA “umbrella” had not been done. Improve International was engaged by MWA to perform this evaluation. The Collective Impact Report (Improve International, 2012) aimed to document MWA’s effectiveness in the field and seek concrete evidence of the value-added of working in coalition, using the five conditions of collective success identified by Kania and Kramer (Kania & Kramer, 2011).

While the evaluation focused on working in partnership to implement field programmes overall, it focused on the MWA Ethiopia Programme (MWA-EP), because it is MWA’s largest and longest-running programme, has multiple and changing partners and support from public and private donors. The evaluation encompassed:

- A comprehensive review of internal programmatic documents and data and external evaluations;

- Interviews with 29 programme stakeholders: 13 in the U.S. and 16 in Ethiopia; and

- Field visits.

MWA Secretariat staff Rafael Callejas and Susan Dundon presented the results and recommendations from the Collective Impact Report to the MWA Board and to the MWA-EP partners. Findings from the evaluation will also help to inform the new strategic plan that is being developed by the MWA Secretariat for approval by the Board of Directors in late 2013 (the Revising stage of the Partnering Cycle (Tennyson, 2005)). The article summarises the report’s findings as well as the response and feedback from the partners involved. MWA’s plans for addressing recommendations are also described. This is all consistent with the role of the partnership broker in helping partners to anticipate what is required to move the partnership forward effectively and use evaluation as a key component of good partnering practice. A brokering unit like the Secretariat is well placed to encourage ‘action learning’.

And this was borne in the findings. The vast majority of interviewees thought the partnership had improved over time. Many interviewees attributed this to the support provided by the MWA Secretariat in the US or the programme-specific secretariats in fulfilling the Planning, Managing, Resourcing, and Implementing roles of the Partnering Cycle (Tennyson, 2005). The most tangible benefit cited by partners is learning and peer support that allows each individual member to improve its effectiveness based on the experiences and insight gained from the others. This learning almost always happens as a result of the Programme Management Group meetings built into the program and organised by the Secretariat. One of the major recommendations is that this learning needs to be systematised and documented to share within MWA itself and the global WASH sector overall.

Does working in partnership result in greater impacts than working independently?

Because of a lack of comparable longitudinal quantitative and qualitative data, it was difficult to assess how successfully the partnership has achieved effective impacts and sustainable outcomes because the end-of-implementation and ex-post evaluation documentation available at the time of the study did not use the same indicators or the same locations. However, in recent years the MWA Secretariat has worked with outside experts to establish a common monitoring framework and incorporate it into the overall policies and procedures that each partner must endorse. MWA-EP is now collecting comprehensive output, outcome, and impact data under a common monitoring framework it should be possible to provide more quantitative analysis of effectiveness and impact in future iterations of this report. Measuring is one of the important roles of the partnership broker in the partnering cycle (Tennyson, 2005), and demonstrating effectiveness and impact will help the MWA Secretariat in attracting new resources.

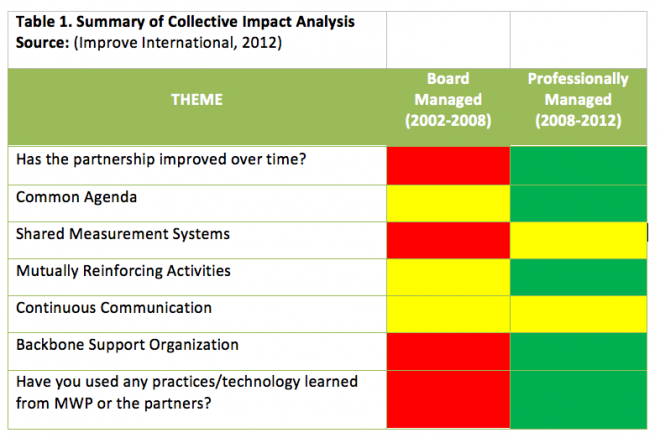

Table 1 below summarises the Collective Impact analysis based on the two phases of the partnership: while MWA was board managed (founding to 2008) and professionally managed through the Secretariat(2008 to present). The benefits of the MWA Secretariat’s role as a partnership brokering unit are evident here. Green means that the partnership generally meets the criteria for the Collective Impact area; yellow indicates that some improvement could be made in that area; and red indicates that the partnership does not meet the criteria for that area.

What is notable from Table 1 is the clear improvement of the collective impact indicators (from red to yellow to green) during the two phases. These conclusions were especially echoed by interviewees in Ethiopia, who described their experience in the first phase as working ‘together’ rather than ‘in partnership’ because they received funds from the same donor while pursuing their projects independently with little overall cohesion. Both US and Ethiopian stakeholders agreed that the hiring of US staff and the expansion of the Ethiopia Secretariat in 2008 and further in 2010 added a level of commitment and additional attention to the program that opened up space for partners to discuss common policies and strategies, harmonise costs, and pilot innovations. The role of the Secretariat as partnership broker – or backbone support organisation- in effecting these clear improvements is reflected in language from both Kania & Kramer and the Partnering Guidebook:

In the best of circumstances, these backbone organizations embody the principles of adaptive leadership; the ability to focus people’s attention and create a sense of urgency, the skill to apply pressure to stakeholders without overwhelming them, the competence to frame issues in a way that presents opportunities as well as difficulties and the strength to mediate conflict among stakeholders. (Kania & Kramer, 2011)

A broker may need to adopt a number of different types of behaviours including those of:

- Business manager – Keeping the work results-focused

- Record keeper – Providing accurate, clear and appropriate communications

- Teacher – Raising awareness and building capacity

- Healer – Restoring health and wellbeing to dysfunctional relationships

- Parent – Nurturing the partnership to maturity

- Police officer – Ensuring that partners are transparent and accountable (Tennyson, 2005)

A disaggregation of the responses to specific questions shows an interesting schism between perceptions among MWA’s US partners and their counterparts in the field in two key areas: Ethiopian partners were far more likely to have seen information about the progress of other partners than US-based staff (86% vs. 27%) and to acknowledge applying practices and technologies learned in the MWA-EP in other non-MWA programs (100% vs. 50%). Furthermore, 60% of Ethiopian interviewees felt that communication in the program were sufficient while only 20% of US interviewees felt sufficiently informed.

Key Strength: Learning

The MWA-EP Strategies and Implementation document, adopted in 2011 by all partners to guide the program, includes as a specific objective to operate a learning and policy influence alliance to improve the implementation activities of partners; contribute towards the harmonisation and greater effectiveness of programs, and to raise awareness for the WASH sector in the Ethiopia and internationally (MWP Ethiopia, 2011). The Collective Impact Report confirmed that, thanks to the work of the MWA US and Ethiopia Secretariats, a positive environment for learning has been created among MWA-EP implementing partners over the past seven years.

Many interviewees applauded the MWA’s emphasis on learning. Program Management Group (PMG) meetings – coordinated by the MWA Secretariats and held two or three times per year in each MWA program country/region – are the most common opportunities for learning from peers and other sector experts. For example, interviewees said:

- “… MWA is unique in establishing and coordinating the PMG. The PMG is a special thing [because] we learn from other stakeholders” (ET#3, 2012).

- “Because even the most modest of us don’t really want to be taught or think that we have to learn from another NGO. It works so much better when you put people around a table and in the collaboration there’s potential for some learning together. That’s much more palatable and acceptable – its opens up our organizational eyes to what’s going on or what’s important to other organizations” (US#2, 2012)

When it comes to development, however, collective learning is not enough. To be worth the investment, learning that is generated must be a) applied across programmes to improve effectiveness and b) documented to provide an evidence base for the scale-up of proven approaches and best practices. Partners have shared best practices with each other and adopted pertinent ones in their own WASH programs at the PMG meetings (Siseraw Consultancy, 2012). However, some stakeholders urged for systematic presentation, follow up, and documentation on a small number of learning topics selected each year, as well as guidance on how to implement or scale up piloted techniques and technologies (ET#1, 2012) (ET#4, 2012) (ET#6, 2012) (ET#8, 2012). “We need to document our best practices, success stories, lessons learned and share them across the partnership and outside as well. We need to know about the things that don’t work well“(MWA Ethiopia Program, 2011).

Figure 1 illustrates examples of knowledge transfer among MWA-EP partners over the past seven years. Each arrow represents something that one partner learned and implemented from the work of another. Prior to the Collective Impact Report, none of these dots had been connected. This schematic reflects what was expressed repeatedly in interviews and led to the report’s recommendations on focused learning, better documentation and improved communication. The MWA Secretariat is responding to this by building in a formal Learning Agenda to its new program in Latin America, and experimenting with a new global platform (www.akvo.org) that can facilitate learning across programs.

Recommendations

The MWA has great potential in developing a robust evidence base for best practices, and this would certainly be of service to a sector where information on what works and why is fragmented and insufficient. Yet there is a much more ambitious role for which the MWA is well suited. The world is changing rapidly, with climate change, urbanization, food insecurity, water scarcity, and rapidly growing populations. All of these will be obstacles or opportunities for the WASH sector. This is an excellent time for MWA to lead the sector in considering next practices (which are forward looking), and will be the Secretariat who continues to broker these conversations. It is recommended that the MWA use methods such as appreciative inquiry to engage its partners, donors and other stakeholders in developing, implementing, and sharing next practices. These visioning exercises can inform in turn the considerations of the best role for MWA, resources needed, and advocacy themes.

Figure 2 shows a possible theory of change for the organisation developed jointly by MWA and Improve International that examines the role and direction MWA can take to: 1) be a conduit for collective learning that improves its member’s global WASH programs and enables the members themselves to scale up use of best practices and 2) documents collective learning systematically to build an evidence base for advocating with donors and the sector overall for more and better targeted investments in WASH. While some individual member organisations have similar efforts, the combined voice of the members, facilitated and amplified by the MWA Secretariat with documented evidence, has potential to be much more powerful in effecting transformation of the global WASH sector.

Figure 2 “Working” Theory of Change for MWA

This theory of change was articulated based on comprehensive internal and external reflection on the partnerships created by MWA over the past 10 years. When presented to both the MWA Board and staff in Ethiopia, the schematic was very positively viewed as a realistic image of what the on-going role of MWA should be. There was also debate on how to include the role of influencing government policy and action, which some, (especially in Ethiopia) felt was missing from the diagram. We anticipate that the theory will be dynamic as the partnership continues to mature.

Leading the Future: Recommendations for MWA

The Collective Impact Report included the following recommendations (Improve International, 2012):

Advocate to the Sector

- MWA Secretariat should collaborate with other sector conveners to engage major WASH donors in the conversation about next practices;

- As the methods and outcomes of learning are better documented by the Secretariat, MWA should purposefully share this powerful evidence – for example, at sector conferences or in publications – to advocate for the power of partnership.

Expand Collaboration with Members

- Interviewees value the MWA Secretariat in certain of its partnership brokering roles – as a generator of resources, a leader of advocacy, and a facilitator of learning — rather than simply coordinating implementation and reporting. It is strongly recommended that a facilitated global summit be held to determine the most useful role(s) for the Secretariat and for the MWA partnership overall moving forward.

Systematise and Prioritise Learning

- The MWA Secretariat, with varied programmes in different regions, is particularly well-positioned to make a comparison of alternative approaches, their costs and benefits over time, and the scalability of their methods, which would be useful to the sector.

- The MWA US and Program Secretariats should coordinate the selection of priority learning themes to discuss at PMG meetings and ensure systematic follow-up.

Monitor and Evaluate Rigorously to Prove Impact

- The MWA Secretariat should ensure that each phase of the program has end-of-project and post-project evaluations that can be compared to baseline evaluations. This is the only real way to document impact and to understand what is working and what needs improvement. Those reports should be shared publicly: results and information can be used in advocacy efforts.

- All partners should commit to measuring at least a small set of indicators the same way, in the same places, over at least 3 years to be able to determine true progress.

Reflection Leads to Better Work

The process of having an external independent evaluation of MWA and its model has been an extremely valuable one for a number of reasons. First, it provided MWA board members and field staff with the opportunity to provide input anonymously and to influence the future direction of MWA based an analysis of the positives and negatives of working in coalition in the past. Perhaps most importantly, the evaluation asked and answered a question that has been repeatedly posed by board members, staff and donors: What is the value-added of working together in coalition? It is clear that the role of the MWA Secretariat as a backbone support organisation and partnership broker has added value and improved the partnership. With the perspective gained from this process and the input gathered from MWA’s key stakeholders, a shared and straightforward vision to achieve collective impact is underway.

Works Cited

ET#1. (2012, July 16). MWP Ethiopian Representative. (S. M. Davis, Interviewer)

ET#3. (2012, July 17). MWP Ethiopia representative. (S. M. Davis, Interviewer)

ET#4. (2012, July 20). MWP Ethiopia representative. (S. M. Davis, Interviewer)

ET#6. (2012, July 18). MWP Ethiopia representative. (S. M. Davis, Interviewer)

ET#8. (2012, July 23). MWP Ethiopia representative. (S. M. Davis, Interviewer)

Improve International. (2012). Collective Impact Report. Atlanta, GA: (to be published).

Kania, J., & Kramer, M. (2011, Winter). Collective Impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review, pp. 36-41.

MWA Ethiopia Program. (2011). PMG Meeting June 1-3 Notes. Hossana.

MWA Ethiopia Program. (2011). Strategy & Implementation Policies, 2011-2016.

MWP Ethiopia. (2011). Strategy & Implementation Policies, 2011-2016.

Siseraw Consultancy. (2012). Final Report of the Assessment of the MWA WASH Program in Ethiopia. Addis Ababa.

Tennyson, R. (2005). The Brokering Guidebook: Navigating effective sustainable development partnerships. International Business Leadership Forum.

US#2. (2012, May 16). MWA Partner representative. (S. M. Davis, Interviewer)

Authors

Susan Davis

Susan Davis

Susan Davis is the Founder & Executive Director of Improve International, an organization focused on promoting and facilitating independent evaluations of water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) programs to help the sector improve. Susan has 21 years of leadership roles in both the for-profit and non-profit worlds, addressing environmental and human health problems domestically and internationally. She served on the boards of the Millennium Water Alliance and the WASH Advocacy Initiative, and is a subject matter advisor to the Foundation Center’s WASHfunders.org site. Susan has evaluated water and other international development projects in 17 countries, including the management of a $1 million WASH in schools project in four provinces in China. Before founding Improve International, she was on the Senior Management Team at Water For People and helped lead them to deliver transformative approaches to water and sanitation problems. She began her work in international development with WaterPartners International (now water.org), and has also worked with CARE USA. Susan is an accredited Partnership Broker through Partnership Brokers Association’s PBAS programme. She holds a Masters of Public Health degree from The George Washington University, and a Bachelor of Science degree from the Georgia Institute of Technology. She is on the steering committee for the Women Networking for Sustainable Futures – Southeast.

Susan Dundon

Susan Dundon

Susan Dundon joined the MWA as a Program Development Officer in 2010. Previously, Susan worked with Médecins du Monde (Medicos del Mundo) implementing community health programs in the Bolivian, Paraguayan and Peruvian communities near Buenos Aires, Argentina. She has also worked extensively implementing water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) programming in the peri-urban slums of Lima, Perú.

[1] MWA members include: CARE, CRS, World Vision, Food for the Hungry, Global Water, LifeWater International, Living Water International, Water for People, Water.org, WaterAid in America, Water Missions International, IRC International Water and Sanitation Centre, and Pure Water for the World.