Abstract: In a long career spanning 25+ years, most of it spent in developing countries and at high levels of management, the author has seen how partnerships live up to the principles of equity, transparency and mutual benefit. In performing multiple roles as a partnership broker, she asserts that this has invariably meant looking at the partnerships through the lens of ethics. In this article she uses one particular partnership to illustrate her insights. Accelerated implementation of a multilateral fund with a focus on achieving quantitative results led to rapid roll out of services for HIV and AIDS; but several questions are posed regarding the ethics around some of the strategies. A retrospective analysis highlights issues around capacity building, monitoring and sustainability. In conclusion, the writer articulates that the UN System did do a noble thing by intervening to save a vulnerable GFATM grant; but the partnerships around the accelerated implementation left questions that need to be answered by any broker.

Dealing with ethical dilemmas – a partnership broker’s personal perspective

Looking back on my career, I have been a partnership broker without explicitly knowing that was the role I was taking on at the time. It has only been due to training and gaining insights on external and internal partnership brokering that I have had the opportunity to reflect back and build a picture of what I actually did. It has certainly helped me to draw out some interesting lessons and insights about the partnering process.

My development experience started in the United States where I worked as the head of an organization that provided recreational activities for young people facing challenges. Since then, much of my professional career has been in developing countries and particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. I have had the benefit of being the Director of the national HIV/AIDS programme in the Ministry of Health in Liberia; and during that period and immediately thereafter, I started with consultancies with the United Nations. This would lead me to my present workspace of serving at high levels of management in the UN system.

Beyond my work with the UN, I also have had experience with multilateral partnerships such as the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (GFATM) and others. I was fortunate to have been at the meeting of the Organization of African Union (now the African Union- AU) in Abuja in 2002 when the GFATM as we know it now was conceptualized by African Heads of State. Kofi Annan, then the Secretary General of the United Nations, lauded the effort and promised to support. In 3 months, Mr. Annan announced a global fund at the United Nations Special Session on AIDS (UNGASS). I wrote the first GFATM grant for Liberia in 2002 while in government; and selected to manage the resources by UNDP in both Liberia and subsequently Nepal where the 2 year old grant was at risk of cancellation due to less than 10% expenditure.

In all of these roles, I now know I was a Partnership Broker.

I have come across several definitions of partnerships, but I have crafted one for my work. A partnership is a strategic alliance or relationship that brings together 2 or more individuals or groups with all of their related resources, skills and abilities to ensure that they achieve agreed results based on their mutual interests and relevant strengths in an equitable and transparent manner.

This definition ensures that the key principles of equity, transparency and mutual benefit are built in. With this definition, we look at ethics in partnerships.

I have drawn out one particular public-public partnership to illustrate this point, reviewing it with the lens of a partnership broker who was a member of the partnership in question, but playing various roles.

The partnership outlined below was successful in that it achieved the desired results as articulated in their core agreements. However, what could have been done differently? What are some of the considerations that a trained partnership broker would now highlight as critical?

The Government of Nepal requested the UN system (all UN agencies in Nepal) to support implementation of their GFATM grant implementation 2006-2009. The UN system established a Management Support Agency (MSA) to partner with the Government and GFATM to accelerate implementation and achieve at least 80% of the indicators within a seven month period.

The partnership was established with a very clear agreement that was signed between the Government and the UN. It spelled out the role of the UN and basically summarised that the UN was to implement the Government’s agreement with the GFATM on its (the government’s) behalf. Government had a major bottleneck at that time which was its inability (legally / administratively) to subcontract NGOs or community-based organisations (CBOs), partners were therefore needed to fully implement the GFATM Phase I grant. Since the implementation plan was delayed by almost 2 years, an accelerated implementation plan was required. The GFATM Secretariat needed to see results within 4 months; but required achievement of 80% of the results within 8 months. This would qualify the country to receive the Phase II component (funds).

The major strategy of the accelerated implementation plan was to recruit NGOs and CBOs that could quickly provide us with the deliverables on behalf of the government. A request for proposals was sent out and over 100 NGOs and CBOs were recruited. The projects were broken down into smaller proportions of the deliverables around the country, and the results reported were managed in a database designed solely for project monitoring and evaluation. All funds were transferred directly to the UN to ensure smooth implementation.

Coordination was essential; and this was done at various layers within the UN and between the UN and government. The highest coordination mechanism was the GFATM CCM (Country Coordinating Mechanism) which was chaired by government and all stakeholders were represented. There were technical committees that functioned around various aspects of HIV prevention, treatment and control; and they were also relied on for technical leadership.

At the end of the 8-month implementation period, around 80% of the results were achieved and Nepal qualified for Phase II of the grant. The project had great strengths beyond the fact that the results were achieved:

- The comparative advantage of the United Nations was brought to bear to support the government in the creation of the UN MSA. It emphasized the UN’s role in the field as a system versus individual agencies.

- At the political level, the UN was well positioned in leading the rescue of the GFATM grant.

- There was also transparency between the UN & government – all strategies were shared and agreed such as the subcontracting of over 100 NGOs / CBOs.

- Government was committed and supportive.

Unfortunately, there were many weaknesses:

- There were too many bosses, too many committees and too little time.

- There was limited capacity of the implementing partners and although at the political level the UN had cohesion and harmonisation, at the technical level, technical officers of the UN wanted to ensure that the funds were divided amongst the agencies in line with their comparative advantages – everybody wanted control over the portion of the funds that had to do with their area of expertise.

- Almost all of the projects were ad-hoc. Hardly any were sustained after GFATM.

Looking back at the implementation, I recall several complaints and issues that were raised with the partnership:

- The UN MSA was accused of a lack of monitoring to ensure quality implementation

- It was accused of undermining government’s leadership role

- Many UN agencies and other external technical partners felt as if the MSA did not do enough to ensure that the required technical capacity was sought

- The capacity of the NGO/CBOs was questioned.

As all of the concerns and issues raised centered around ethics in how the agreement was implemented, the ethics of the arrangement then came into question.

As a partnership broker, the first thing that I have learned in looking back at this experience is that the UN MSA itself was actually playing the role of a broker. As a broker, were the actions of the MSA (which I headed) as ethical as they could be?

- We were acting on the government’s behalf, but government had no input into the selection of the NGOs and CBOs

- Due to time constraints, limited monitoring was conducted. Data was collected and a very strong M&E system was in place, but it was reliant on the reports of the partners.

- We missed the opportunity to bring in others with greater technical capacities to fill the skills gaps

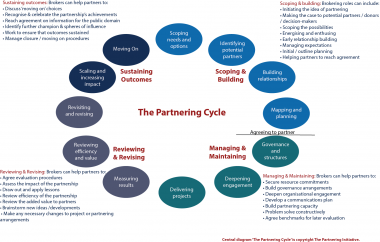

The MSA was created to broker the implementation, and was specifically (in line with the agreement) focusing on scoping, building, managing and maintaining (see partnering cycle below). When one looks at the concerns and criticism, one sees that basically the MSA (although not specified in its agreement) was expected to review and revise, and also sustain outcomes. Given the large investments, that would make sense. However:

- Where do we draw the line on contractual agreements versus doing what is required? We fulfilled the contract, but couldn’t we have done things better?

- How do we use other brokering skills such as negotiating when we know that existing agreements do not address all possible issues that could be addressed within the same envelope of resources? Is it binding on a broker? Is it unethical not to do so?

- Could selection of the NGOs/CBOs have been more inclusive? If government reviewed the terms of reference, did they need to be a part of the selection of the partners? Would it have helped to boost their role and relevance?

- Would it have been better if we had enabled government or others to monitor and provide feedback? Could the review and revise role have been highlighted as a gap and then delegated? We did know during implementation that this area was a gap. The agreement did not require it, but we knew that it was needed.

- Can we be unethical in our partnership when we have done exactly as the agreement articulated?

Needless to say, these questions are not likely to be unique to my own experience. Peers in partnership brokering will have faced similar dilemmas – and no doubt we will continue to do so. The reality is that we deal with complex and often established ways of working where it is often difficult to bring about more than a degree of change at a time. The important thing is that singularly and collectively, we need to keep challenging and catalysing through those small degrees to bring about change.

Also, the aid infrastructure has changed significantly and remains dynamic. This results in evolving partnerships that are sometimes unpredictable. The Sustainable Development Goals present all development stakeholders with a chance to reduce the huge disparities that exist in wealth, power structures and opportunities. Strengthened partnerships will be key to maximising the limited resources available in aid; and ethics around partnerships will be key in determining access to funds.

Author

Author

Sara Nyanti is an Accredited Partnership Broker and development practitioner.