Abstract: In 2012, the Food Systems Innovation (FSI) initiative was set up between four Australian organisations working to improve the impact of agriculture and food security programs in the Indo-Pacific region. The author was assigned to facilitate a stream of work in the partnership, working as an internal partnership broker in one of the four partner organisations, the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). A scientist by training more comfortable with scientific research and its outputs, she had to move out of her comfort zone into the world of facilitated collaboration working amongst organisations with a shared vision but with very different interests and expectations. She had no formal training as a partnership broker when she joined the initiative. The article relates her experiences and insights of her partnership brokering experience, and how it became a test in “becoming comfortable with the uncomfortable”.

Learning to work differently: A scientist’s reflection on acting as a broker for food systems innovation

Introduction

In 2012, I took up the role of broker for the Food Systems Innovation (FSI) initiative, a multi-lateral partnership between four organisations. This meant I was working to influence approaches to agricultural development programming in order to improve nutrition outcomes. It also meant that I had to move out of my comfort zone of a scientist reading and writing science papers to enter the world of working with clients, partners and others to get research findings into use. I had to find ways to bring others along on the journey and ensure our efforts could influence our own practice and the practice of others. These efforts included stimulating interest and engagement in the issue, identifying champions across the partnership, collating existing knowledge on the topic, supporting the co-creation of new knowledge products with partners and clients, and connecting new ideas and people in order to bring about change. I have since come to know that I am no longer just a researcher. I am also a partnership broker. While the practice of brokering for partnerships is fast becoming a recognised tool for triggering innovation (putting ideas and knowledge into productive use), my partnership brokering experience required me to step out of my comfort zone and learn to work in new ways. This reflection shares my experience of being on the frontline.

The project context

The FSI initiative is a partnership between the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT), the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR), the Australian International Food Security Research Centre (AIFSRC), and the Commonwealth Science and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). Its purpose was to strengthen the on-ground evidence of what is working in development, and what is not, through analysis, capacity building and learning activities. Essentially, FSI sought to bring together Australian and international expertise to improve the impact of agriculture and food security programs in the Indo-Pacific region; and identify and foster novel ways of “doing development”.

In doing so, project partners worked together to share ideas that improved development programming and policy decision-making in emerging topics in food systems research and practice. FSI activities were structured around three focal themes: managing for impact; inclusive markets and partnerships and; agriculture linkages for improved development outcomes. This reflection conveys my experience of brokering for the latter theme – strengthening pathways between agriculture and improved nutrition (commonly known as nutrition-sensitive agriculture).

A key driver for CSIRO’s participation in FSI was to improve the science-policy-practice interface. This included assembling, packaging and distributing information on topics of interest; strengthening networks between researchers, decision-makers and practitioners; creating multi-stakeholder platforms, and delivering targeted capacity development activities. Partnership brokering lies at the core of these activities.

The CSIRO led the brokering effort across each of the three themes in FSI. As an employee of CSIRO with a background in health and nutrition, I was tasked with brokering for nutrition-sensitive agriculture (NSA). Two other brokers facilitated the remaining themes and their experiences are not shared here.

Why is partnership brokering important in nutrition-sensitive agriculture?

NSA is typical of many emerging topics in agricultural development. It is a mode of development practice and policy that sits at the interface of a number of (a) different research and practice traditions and (b) different stakeholder interests. Bridging these different interfaces is therefore critical if new and more effective modes of development practice and policy are to emerge. This is where partnership brokering assumes importance.

NSA has other features that make brokering partnerships and ideas critical in moving forward:

NSA in a new topic. Agricultural development seen through a nutrition lens is a relatively new field of research and practice in international development. While the international community has been busy mobilising knowledge and resources to tackle the global burden of nutrition-related conditions multi-sectorally, Australian development programming has been slow to coordinate a strategic response to this problem. This meant that creating awareness within the Australian agricultural development community was required before research and practice ideas could be shared and discussed.

NSA is a wicked problem. It requires a level of knowledge at the interface of multiple sectors – agriculture, food systems, nutrition and health are useful starting points. These need to be bridged and this requires engagement multi-sectorally.

NSA lacks champions. There is increasing interest and experience in NSA domestically in Australia, but few individuals would confidently identify themselves as experts in NSA. Such champions often play a key role in the partnership brokering process, but these were noticeably absent in our case.

Good ideas, but little practice. The conceptual case for investing in NSA is established globally. However there is limited experience of how to do NSA in agriculture programming. This includes how to measure its effectiveness. These gaps underline the need to bridge between what is known and what is being practiced.

NSA has multiple boundaries. NSA sits at the science-policy interface, the agriculture-nutrition interface, and the individual-partnership interface. Partnership brokering was required to navigate these boundaries, and had to deliver several outcomes: it had to create or identify a common language the partnership could use to discuss the issues; it had to create an appropriate space for all participants to engage with the topic and reduce barriers to decision-making and; it had to contribute to some change to the current modus operandi, i.e., have some tangible impact.

The partnership brokering journey – the early days

Commentators have described innovator partnership brokers as ‘agents of change’. While aspiring to becoming an agent of change seems a noble goal, the everyday experience of partnership brokering proved tricky.

Whilst there is some available literature on partnership brokering for innovation, there is however little experiential guidance on how to broker for innovation. I found I needed information about: the skills and traits helpful to the process; the conditions which favoured effective partnership brokering (and those that hampered it); the challenges for researchers acting as partnership brokers; and the lessons from those who had embarked on the journey. In the absence of this information, I had to make it up as I went along.

Partnership brokering without a manual was a daunting task. The brief seemed simple enough: facilitate a process enabling a diverse group of individuals to work together towards a common end. My goal was to assemble a small group of interested individuals and motivate them to think creatively about ways that nutrition concerns could become embedded in agricultural development. I needed to steer the group towards achieving the goals set out. Having some background in nutrition and health, it was expected that brokering knowledge was a key component of the partnership brokering role.

Unsurprisingly it wasn’t long before the plan began to unravel.

While our partnership brokering goals in FSI were clear, the means by which to achieve these were less clear. To complicate matters, partnership facilitation in our project manifested differently across levels and purposes. My NSA Working Group was focussed on trialling approaches that might lead to strategic or operational change. In contrast, the organisational-level partnership had the task of steering and directing the project and maintaining a commitment to engage institutionally despite the challenges.

I began the job of facilitation by setting up a Working Group comprising of individuals who had expressed interest in contributing to either their own learning on NSA or stimulating interest in this area within their own networks. Essentially, I wanted to use a multi-stakeholder platform to drive a mutually-defined and solutions-focused agenda. The goal of this process was to enable a shift in ‘how we did development.’ It would be inclusive, participatory and efficient.

I organised fortnightly meetings, initially for an hour each time. There was always a mutually-agreed agenda emailed well before the meeting and I always made an effort to follow up after each meeting. Apart from the initial couple of meetings, we mostly used teleconferencing facilities to hold discussions. On occasion, some individuals would meet informally in-person, when travelling interstate on other business. Our conceptualisation of the innovation process was that if we brought people together, they would share ideas, learn and change practice. They would innovate.

Almost all of the members of the Working Group were representatives of FSI partners. The group worked together to hold two NSA learning events which brought together researchers and practitioners and showcased cross-organisational efforts in NSA programming. We also tried to inject new thinking about NSA into existing agendas by influencing upcoming events. Knowing that a particular event was in the planning stages, we would try to harness the opportunity to include an NSA perspective, however small or trivial, to the existing agenda.

It was not long, however, before the vision of becoming ‘a change agent’ disappeared and was replaced by the demands of being ‘an event organiser’, ‘a conflict mediator’ and a ‘motivational coach’. These demands simply presented themselves in managing the Working Group – in the sheer effort it took to foster individual and group relationships, organise meetings, and negotiate diverse organisational interests.

In reality, the pace and volume of work at times was all-consuming, and placing trust in the innovation process was challenging. The biggest reality check came when the most interested and committed members of the initial Working Group were on the whole too busy to actively participate in activities that required a commitment of longer than 30 minutes to an hour.

As a member of the Working Group, there were expectations to meet, such as, following up on conversations within your own organisation, reading documents and reflecting on them, and scheduling time to meet. These commitments took energy and time. Individuals participating in the Working Group were formally unallocated to the project and were unpaid, volunteers. Meaningful discussions that delivered meaningful outcomes were few and far between. Being ‘too busy to learn’ became a constant hurdle in mobilising support for the co-creation of knowledge across all partners. In retrospect, however, the co-creation of knowledge was the glue that held the partnership together and enabled us to trigger change.

After a disappointing slow start, we realised our mistake of having overlooked a critical first step. FSI was operating under the assumption that the case for investing in efforts to improve nutrition through agriculture was both understood and accepted locally. Neither was true. While at the time of project inception, it was true that well-articulated pathways between agriculture and improved nutrition were beginning to emerge internationally, only a small group of us were convinced that the goal of improving nutrition was worthwhile pursuing seriously.

Taking a step back to move forward

We realised we needed to step back and redirect effort on consensus-building and mobilisation. Each FSI partner arrived at the partnership with a range of assumptions, expectations and wish lists. Even before consensus-building began, a period of orientation was needed. This included conducting an internal organisational stocktake to understand whether NSA existed in any form in our own organisations and how it manifested at the program or policy level. I called this process sense-making. It was essentially asking the question: Where do we fit in the bigger picture? This period was crucial for building trust, affirming commitment to the partnership and progressing towards originally stated goals. We embarked upon an intense period of knowledge sharing and relationship building.

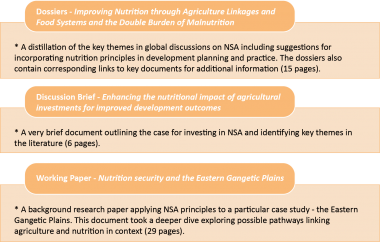

When energy and enthusiasm began to wane, the need to work differently became critical. Given that trust across partners was still being built in some pockets, organisational mandates and cultures were varied, and given the time and resource constraints to participate in extended activities, we made the decision to work differently. The NSA theme redirected efforts to creating synthesis documents such as ‘dossiers’ which could be easily digested, had multiple uses, and were easily accessible. Internally, we referred to these pieces as ‘boundary objects’ – they were concise, objectively and simply written knowledge products able to bridge multiple boundaries. They were created using desk-top research, they referenced seminal works, and were made publically available on the FSI website. They were not perfect, but they were useful.

CSIRO took the lead in creating the first couple of products but some of the later documents were jointly created with partners. All products addressed themes of mutual interest. Table 1 includes some examples.

Table 1: Examples of boundary objects used to catalyse interaction among diverse partners working in constrained environments. All these documents are available at http://foodsystemsinnovation.org.au/

While these products were used by stakeholders in various ways and to varying degrees, one particular product had considerable traction with partners early on. The first dossier – Improving nutrition through agriculture linkages – essentially an introduction to key themes for NSA, was a successful boundary object in a number of ways. The document helped build credibility and trust in CSIRO to deliver accessible and useable products beyond traditionally dense and lengthy science papers. It also synthesised key themes in the literature which helped readers identify key pathways between agriculture and nutrition. Essentially, it demonstrated that researchers could communicate science differently. Sufficient momentum was achieved in disseminating this piece. It was not long before I was invited to contribute to several strategic policy and programming initiatives including:

- DFAT’s new Strategy for Australia’s Investments in Agriculture, Fisheries and Water;

- Membership of the design team for TOMAK – Timor-Leste’s Agricultural Livelihoods Program;

- Co-authorship of DFAT’s Operational Guidance Notes on NSA Programming

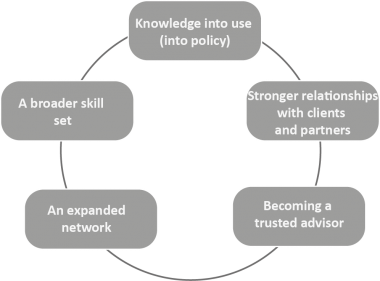

While these successes might appear trivial, I clearly remember Day 1 on the Project (2 years prior) when the first mention of NSA was met with blank expressions, confusion and in some cases dismissed as fanciful. Partnership brokering has turned this around because it has involved bringing a range of different stakeholders into a journey of reflection, analysis and documentation. Figure 1 shows some of the broader impacts of brokering for the FSI initiative.

Figure 1: Some of the impacts of partnership brokering for triggering innovation

Enabling conditions for effective partnering

While these products helped foster interaction among our partners and stakeholders, there were additional enabling factors at play which helped us achieve momentum and meet our partnership goals.

Timing and demand were critical factors to our success. The products we chose to focus on were aligned to emerging international themes as well as being aligned with current priorities for our partners. They were largely demand-driven by ACIAR and DFAT staff who needed up-to-date information quickly. The products met a need which could not easily be met by others. We were filling a gap. A change in government also provided the partnership with an opportunity to challenge the status quo and advocate for change. We linked the government’s new focus on women and economic empowerment to the opportunity for enhanced nutrition for women and girls. We also connected the government’s closer regional focus to the rising tide of obesity in the Pacific, signalling the need to view nutrition using a systems lens.

The content and intent of the pieces we produced had to be negotiated among all partners as they had to meets the needs of most. Once delivered, the products became objects which facilitated interaction, generated feedback and strengthened relationships. The delivery of these products also created confidence in our partners that the project was yielding results. These interactions paved the way for more inclusive participation and have since invited opportunities for further engagement.

My approach to partnership brokering was always practiced in the spirit of inclusion, respect and transparency. Working with these particular values in mind has helped me to build trust and foster good relationships. When I completed the Partnership Brokers Training course much later in the process, I learned that these values play an important role in the success or otherwise of partnerships. I’m convinced working in this way yielded better outcomes.

Finally, and most importantly, I found success once I was empowered to make decisions and act autonomously. A partnership broker seeking innovation requires independence to work in a way that best suits the situation at hand. The settings can be complicated and without sufficient autonomy, the risk to relationships, trust and progress increases.

Facing some professional challenges

The partnership brokering process was shaped by many factors, some more predictable than others.

Convincing research peers working in food security that nutrition was important to development outcomes was an expected challenge. Creating legitimacy in a novel area of work was always going to take time and effort.

Convincing peers of the value of partnership brokering was an unexpected challenge. I encountered a common view among colleagues external to FSI that pure research was somehow more meaningful, prestigious and worthy of pursuit than partnership brokering for impact. On occasion, I found myself in a position where defending the value of our work became necessary and organisational support for partnership brokering was hard to find. Traditional research-based performance systems tend to reward traditional science activities and outputs and our efforts did not neatly align with these targets.

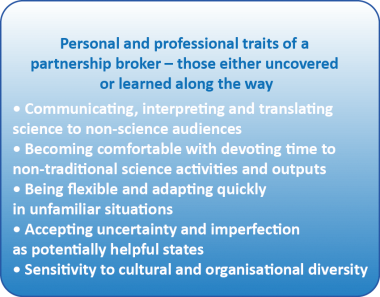

Partnership brokering also required practicing a range of skills specific to process facilitation – a skill-set not naturally in abundance among scientists. Building trust quickly, communicating cross-culturally, inspiring and facilitating participation, organising and managing meetings, mediating conflict and being in possession of a service-delivery mindset were just some of the skills needed on the journey. For me, some of these skills were either uncovered or learned over time. In time, the partnership brokering experience became a test in ‘becoming comfortable with the uncomfortable’.

Figure 2 A collection of personal and professional attributes which helped me foster knowledge creation and relationship-building

Learning from our experience of partnership brokering for change

When first embarking on the partnership brokering journey, the FSI team were in possession of well-laid plans and at the time, expectations that seemed reasonable. In time, we learned to expect the unexpected. The following lessons were learned along the way:

- Partnership brokering as a researcher requires a shift in mindset on a number of levels

In many ways, partnership brokering for innovation is a reorganisation of traditional approaches to science. The science comes from lessons in implementation and delivery. Being open to new ways of creating knowledge and valuing different knowledge types equally, is important to the innovation process. Mustering pride in the creation of non-traditional products also helps with acknowledging success.

- Partnership brokering is not a linear process and there will be many roadblocks along the way – this is a good thing because that’s when learning happens.

Compromise and experimentation were keys to success. While plans are a good starting point, letting go of plans can yield better results. In time, expecting the unexpected made the learning process easier.

- Partnership brokering is time-consuming, requires specific skills and needs considerable investment to be successful.

For those of us in FSI who were on the ‘partnership brokering frontline’, days and weeks were consumed in nurturing the process. Organisational incentives available to formally recognise the time spent in conversations, in reflection and planning, and in problem-solving were difficult to find. Partnership brokering requires skills in process facilitation – and these skills need to be acquired – and valued.

- Empowering a partnership broker with sufficient autonomy is absolutely critical to success.

When facilitation was first attempted in the project, the conditions were very different to those that are present now. The partnership brokering process and conditions were initially dictated by individuals who would not be doing the facilitation. In time, a partnership broker develops an intimate understanding of the brokering topic, the political climate, the cultural sensitivities and the likely constraints before them and develops necessary key relationships. The partnership broker must be sufficiently empowered and entrusted to make decisions perceived critical to success.

- Success comes in a variety of ways.

Products and outputs are artefacts of success, but so are successful partnerships, processes which inspire innovation and lessons that are freely shared. In organisations where innovation and impact are valued indicators of success, support for activities such as partnership brokering may require organisational and cultural shifts so that these new ways of doing science gain better traction.

Author

Lucy has a background in international health, agriculture and nutrition links and research ethics. She has held roles in research and management across various sectors including biotechnology, public policy and health. She currently works as a social scientist at the CSIRO in Brisbane, Australia.

Lucy has a background in international health, agriculture and nutrition links and research ethics. She has held roles in research and management across various sectors including biotechnology, public policy and health. She currently works as a social scientist at the CSIRO in Brisbane, Australia.